The antigovernmental protests in Sri Lanka have stopped for the time being.

The large protest crowds that surrounded the president’s office for months during Sri Lanka’s greatest economic crisis since independence are long gone.

Instead, a large number of carollers sung to the public from the other side of the Presidential Secretariat’s heavily guarded fences. An 80 foot (24 m) Christmas tree stood next to the structure, serving as the focal point of a setting that included decorations, food stands, and musical performances. A huge throng gathered at Galle Face Green, a seaside promenade, as fireworks rang in the new year.

All of this was a part of a festive area that the government had planned as a year-end tourist destination in Colombo, Sri Lanka’s capital.

However, there is little to celebrate for many people who used the location as their “ground zero” for Occupy-style rallies from April to August and called for the resignation of their leaders.

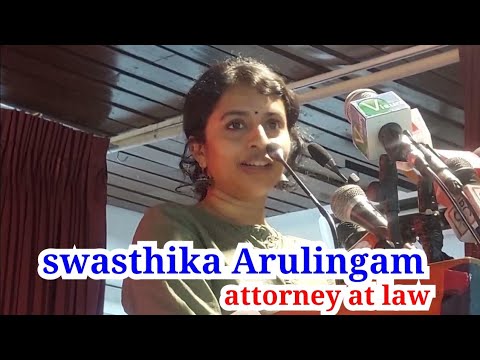

Swasthika Arulingam says, “It’s disgusting.” It’s an offensive display of resources that this nation is denying to its most vulnerable citizens and wealth that this nation does not own.

She continues by saying that the festival illumination is especially upsetting given that the government-run electricity authority has lost 150 billion Sri Lankan rupees (£344 million) this year.

Extended daily blackouts are once more a possibility. The cost of basic foods, transportation costs, and children’s school supplies is rising. Additionally, the harsh tax increases that the new year will bring will only make the situation worse.

According to Ms. Arulingam, there is currently “a kind of pseudo-stability,” but locals are under a lot of stress as it becomes more difficult to make a living. People in Sri Lanka had severe shortages of food, fuel, and other necessities for much of last year as a result of a number of government policies that followed the pandemic, which had left the nation on the verge of bankruptcy and drained its foreign reserves. Long fuel lines and power shortages caused widespread unrest for months, which culminated in the occupation of Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s official residence and office in July, compelling him to leave the country.

There have been calls for early elections now that it has been six months and more suffering is expected. Ranil Wickremesinghe, Mr. Rajapaksa’s replacement chosen by the parliament, has mostly refrained, but it is anticipated that local government elections would be held next month after a one-year delay.

Following his promise that he would not permit “fascists” to “tear up our constitution,” Mr. Wickremesinghe has also retaliated against the anti-government protest movement and its leaders.

What led to Sri Lanka’s crisis?

“We need new faces if we want change,”

Children in Sri Lanka go hungry as food costs rise.

Currently, “Any type of demonstration is restricted in Sri Lanka,” said Shreen Saroor, a human rights activist from the region. He has maintained his authority to carry out his duties and to use the military to take over the nation should the need arise.

Ms. Saroor draws attention to the fact that Mr. Wickremesing has continued to exercise executive presidential authority, allowing him to send out security personnel and order detentions in accordance with the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA).

According to critics, the Rajapaksas strengthened the system over their two decades in office, which greatly concentrates power in the hands of the president and lacks the necessary checks and balances. One of the main demands of the demonstrations last year was to abolish it and amend the constitution.

Catholic priest Father Jeewantha Peiris is one of the protest leaders accused of a number of offenses under PTA, including assault and unlawful assembly. In court, he is retaliating against what he deems “baseless claims.” He refers to the former six-time prime minister as “another offender who had been associated with the corrupt system” and claims that when Parliament elected Mr. Wickremesinghe as president, they “completely abandoned” the people.

He claims that although the crisis appears to have been resolved, its underlying roots remain unaddressed. “Corruption continues to exist. Malnutrition and pharmaceutical shortages are actual problems. People in poverty cannot handle this inflation.”

According to him, the government is frightening people like him, but “this issue will not be resolved unless they bring to account those who have perpetrated economic crimes and abused human rights.”

In the village of Doloswala in the south-central Ratnapura district, Father Peiris serves as the parish priest for a large portion of Tamil-minority rubber estate workers. He claims that Sri Lanka’s poorest and most vulnerable people have been neglected by previous governments.

He argues that when the epidemic hit, the villages became sick in great numbers but were unable to isolate themselves in their homes or acquire vaccines. Additionally, because the schools were closed, their children suffered with no chance of distance learning.

Mothers would visit his cottage and beg me to feed their malnourished kids, he claims. As a priest serving among them, I was unable to stand by and witness their daily suffering.

The parishioner, who had black hair and a spotless white cassock, regularly attended the demonstrations on Galle Face Green. His message was that a national movement for structural transformation was required in the nation.

Without regard to ethnicity, creed, or ideology, he says it was the first time Sri Lankans came together in a fight for the common good: “We had no divisions among us and we all felt we were victims.” Daily protests that started on April 9 swiftly took on the name “GotaGoGama,” which combines the Sinhalese term for “village” with the demonstrators’ demand that Mr. Rajapaksa resign as president.

The small community, which was set up in front of the Presidential Secretariat, produced demonstrations, candlelight vigils, stage productions, and a sizable library of donated books, all of which aimed to increase political literacy.

It organized open discussions concerning minority differences, remembered historical crimes committed in Sri Lanka, and strengthened after being mercilessly besieged by thugs loyal to the government.

But by July, as demonstrators’ resentment over Mr. Rajapaksa’s refusal to step down from government mounted, the crowds had gotten bigger and more unruly.

As Mr. Rajapaksa fled to the Maldives and eventually announced his resignation in the days following the president’s home and office being stormed, security forces acting on the orders of his successor reclaimed the two structures and raided the GotaGoGama protest camp, arresting protesters and tearing down their tents.

The so-called “aragalaya,” or people’s struggle in Sinhala, has largely died down with many of its prominent players now in jail, in court, or under constant observation.

According to Dr. Paikiasothy Saravanamuttu, the founder of the Centre for Policy Alternatives, “it was a national movement, a vision of what Sri Lanka should be,” but “the middle class has forsaken it, the ordinary community groups have all deserted it.”

He claims that “[Mr Wickremesinghe] successfully adjusted the narrative to indicate there is a good and a bad aragalaya, and what we are now grouped with is the terrible aragalaya.” Dr. Saravanamuttu contends that some people, particularly older Sri Lankans, see Mr. Wickremesinghe as the greatest candidate to revive the struggling economy, but he must stick to a fair schedule for local and presidential elections.

He continues, “The sooner we get some legitimacy, the better.” But from Ranil’s perspective, he wants to lead this nation and won’t take any actions that would be seen as a strong rebuke of whatever administration he leads.

People in Sri Lanka will continue to struggle as they wait for an IMF bailout for US$2.9 billion (£2.4 billion) and funding guarantees from China and other bilateral creditors. In especially in areas outside of Colombo where people are poorer and would be worse hurt by growing food prices and fuel shortages, Dr. Saravanamuttu warns that a new round of public protests is on the horizon.

People will show up, he predicts, “not because they want constitutional change or to stop impunity, but because they can’t survive.” And that could be more deadly since it would be impromptu and have a “them vs us” component.

Whatever happens next, the protest movement of 2022 has made a lasting impression on Buwanaka Perera, a 27-year-old social media activist who assisted in organizing the GotaGoGama marches.

People confronted demons head-on and gave them the finger, he claims.

“Gotabaya was successfully sent back home. There is no turning back if folks were able to send him running and hiding in [army] camps and on islands.”