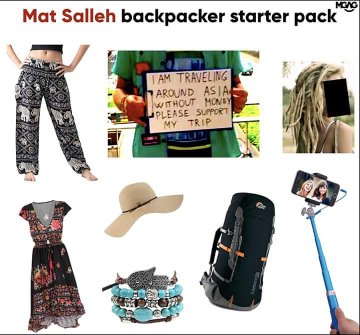

Who are the ‘begpackers’ attracting attention across Asia

From Bangkok to Bali, Seoul to Suva, some low-budget travellers have earned themselves a bad reputation.

In recent years, social media users across the Asia-Pacific, particularly in South-East Asia, have condemned so-called “begpackers” — mostly Caucasian foreigners who seek the charity of passers-by, usually to fund their travels.

“We hate them,” Munira Mustaffa, a Malaysian counterterrorism analyst who has studied in the UK and US, told the ABC.

South-East Asia is not a “personal playground” for Westerners to “come to seek ‘spirituality’ and treat us as props for your self-discovery,” she said.

Drawing vitriolic responses online from many locals like Ms Mustaffa, will governments start to take a harder line on free-loading travellers?

Begpackers: Who are they?

Those heaped under the begpacker umbrella are a fairly diverse bunch.

There are those literally begging with a sign that says “help me fund my dream trip”, to those selling sketches or postcards.

Others busk with ukuleles or other instruments.

Joshua D Bernstein, a tourism researcher from Thammasat University in Bangkok, told the ABC that a majority of begpackers he interviewed were from Russia or the former Soviet Union.

Early in 2019, a Russian couple were arrested in Malaysia for swinging their baby around whilst doing a bizarre musical “performance” at a popular tourist street in Kuala Lumpur.

Then there are the Western travellers accused of conducting scams.

A German man named Benjamin Holst — whose swollen leg is believed to be affected by the rare macrodystrophia lipomatosa disorder — grabbed media attention around Asia in recent years.

While photographed across the region sitting on the street begging, Mr Holst’s regularly-updated Facebook page revealed a different side of his exploits.

He posted photos boozing, eating lavish meals and posing with various local women. Deemed a “conman” by many, he was subsequently reported to have been blacklisted by Thai immigration and barred by Singapore.

Will begpacking be tolerated?

In June, Balinese authorities suggested they would crackdown against Westerners allegedly begging on the island’s streets.

“Foreigners that don’t have money or who pretend to be poor, we will send those people to their embassies,” said Indonesian immigration official Setyo Budiwardoyo said at the time.

Mr Subdiwardoyo said that the issue had “caused a lot of problems” and that those encountered by authorities were mostly Australian, British or Russian.

The Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade said it “encourages travellers to take personal responsibility for their safety, finances and behaviour overseas, including obeying the laws of the country they are visiting.”

Ross B Taylor, president of the Perth-based Indonesia Institute Inc., told the ABC that “Australia charges every Indonesian citizen $140 just to apply for a visa to holiday in Australia.”

“It is a bigger enough affront to our neighbours that we are welcomed into their country free of any visa fee, yet [begpackers aim] to ‘save’ even more money … it offends Bali’s Hindu culture,” he added.

Juka, who goes by one name, told the ABC that begpacking had become an “epidemic” in parts of southern Bali like Kuta.

He runs the Bali-based Farmers Yard Hostel, which offers free stays to those who contribute to upkeep of the hostel.

“But there are heaps of people who just come and borrow, and take,” said Mr Juka, who added that the influx of begpackers had compelled the hostel to introduce new rules against freeloading.

Many of those expecting freeboard and other amenities were affiliated with the so-called Rainbow Gathering movement — an American-born counterculture opposed to consumerism and mass media — he said.

“There are no beggars,” Babua Murjani, a member of the Rainbow movement in Bali, told the ABC.

“Artists just performing as they travel, those that understand that they are not participating with dying capitalistic consumer culture.”

“To come out and perform art on the streets takes courage, it’s a form of revolution,” he added.

Are double standards being applied?

Thailand has begun to more strictly enforce its rule of requiring foreigners to have at least THB10,000 ($480) at immigration checkpoints, according to expat forums.

Nevertheless, a recent survey by UK-based market research agency YouGov showed that 46 per cent of Thais have a positive view of begpackers, while only 10 per cent have a negative impression.

In Thailand, as in other parts of South-East Asia, there is a culture of almsgiving.

Mr Bernstein said that budget travellers were attracted to the region for its the low cost of living and “friendliness of the people … culturally people are not confrontational in Thailand or throughout most of South-East Asia.”

Online criticism of begpackers was indicative of ‘callout culture’, he added. For Helen Coffey, deputy travel editor for The Independent, we should be careful to judge begpackers too quickly.

“There’s an uncomfortable assumption that every white person in Asia has independent means and a rich family back home to call upon should they run out of money,” she wrote in 2017, as begpackers began copping lots of criticism on social media across South-East Asia.

Max Geraldi is originally from Java in Indonesia and has travelled for more than 10 years around Europe, South Asia and the Middle East by doing odd jobs including street performances.

He told the ABC he thinks “any type of money-making that requires performance, then it’s not begging. If there’s something to exchange — like entertainment — it’s not begging.”

But foreigners in South-East Asia are judged more harshly for busking, as the begpacker label shows, Mr Geraldi said.

Many other South-East Asians, however, note the inequity of the fact that most Western travellers get visa-free entry into their countries.

Citizens of the region, meanwhile, are required to undertake time-consuming medical checks, provide bank statements and other paperwork, and pay fees for visas to visit Europe, North America or Australia.

“Do they realise how much we have to spend just to get visas to visit their countries? And here they are parading themselves as needy in a context where poverty really means living in sub-human conditions,” Nash Tysmans, a Filipina community worker told the ABC.

The ABC’s inquiries prompted Ms Tysmans to write an op-ed in the Philippines’ most widely read English language newspaper, The Inquirer.

“Imagine the lengths we take to open our doors to tourists and extend arms and legs as part of our culture of hospitality to make outsiders feel at home,” she wrote