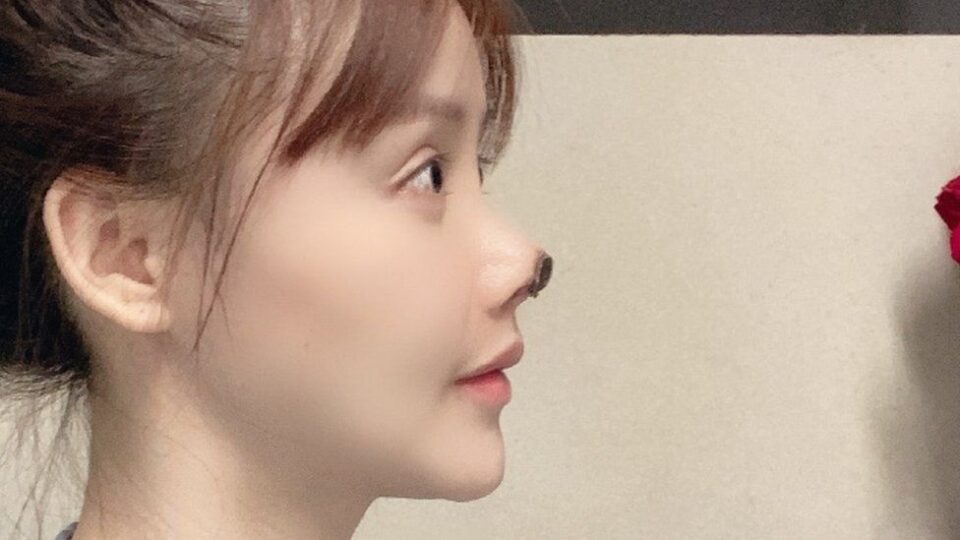

Like many of her peers, 23-year-old Ruxin scrolls her social media feed every day, but she is looking for something very specific – updates about cosmetic surgery.

Ruxin is planning to have “double eyelid” surgery where the surgeon creates a crease on the eyelid, that she hopes will make her eyes appear bigger.

The Guangzhou resident logs on to the Gengmei app regularly to hunt for the most suitable surgeon.

“There are so many clinics in the city but I want to make sure I go to a good one. It’s my face we’re talking about,” she told the BBC.

Gengmei, which means “more beautiful” in Chinese, is one of several social networking platforms in China dedicated to cosmetic surgery, where users leave status updates about all things plastic surgery, including liposuction and nose jobs.

Search results can be filtered by regions, treatments and clinics, among others.

Since its launch in 2013, Gengmei’s users have surged from 1m to 36m. More than half are young women in their twenties.

Their popularity is an indication of the changing attitudes towards cosmetic surgery in China, which now performs more operations than any country in the world after the US.

According to a Deloitte report, the market in China has almost trebled in value in four years to some 177bn yuan ($27.3bn; £19.7bn) in 2019 – an annual growth rate of 28.7%, well above the global rate of 8.2%.

If this continues, China could become the world’s largest cosmetic surgery market by the middle of the decade, according to The Global Times.

While the most popular procedures include those creating “double eyelids” and V-shaped jaw lines, new surgery fads come and go, with the latest being pointy elf ears, according to reports.

Members of Gen Z – those born after 1996 – are not shy about getting such procedures done despite the topic being seen as taboo in the past.

Ruxin, who works in fashion retail, said that her friends “openly talk about getting cosmetic procedures”.

“Even if people don’t advertise that they have gotten something done, they won’t deny it if you ask them about it.”

More regulation needed

However, China’s cosmetic surgery boom comes with its drawbacks.

According to a Global Times report, the country had more than 60,000 unlicensed plastic surgery clinics in 2019.

Those clinics were responsible for around 40,000 “medical accidents” every year, an average of 110 botched operations per day, the report added.

In one of the most high-profile cases, actress Gao Liu shared images online of a cosmetic procedure that left her with necrosis of the nose, meaning the tissue at its tip has died.

She said that she will need more surgery to fix it, but the complication has already cost her more than 400,000 yuan in film deals.

Meanwhile, her attending physician was suspended for six months, and the hospital fined 49,000 yuan.

Many internet users said the penalty didn’t go far enough.

“This is the punishment for crippling someone?” one user wrote as she demanded better regulation of the industry.

Last month, China’s National Health Commission announced a campaign targeting unlicensed cosmetic surgery providers, including investigating customer complaints more swiftly.

Why take the risk?

Many people in China place a great deal of importance on looks and the quest to “be beautiful” is driving the cosmetic surgery trend, experts told the BBC.

Dr Brenda Alegre, a gender studies professor at the University of Hong Kong, said that “conforming to ideals makes one more desirable, not just for romance, but for jobs”.

In China, job applicants are often required to submit a photograph. Some job advertisements also specify physical requirements, especially for women, even if they are not needed to do the job.

A 2018 Human Rights Watch report highlighting China’s sexist job ads cited examples including one looking for an “aesthetically pleasing” clothing sales associate, and another for a “fashionable and beautiful” train conductor.

And with the internet creating a whole host of new job opportunities – all of which ride heavily on one’s looks – experts say there is a renewed focus on appearance, more than ever before.

“To a certain extent, beauty can bring more career opportunities – for example, there is monetisation in live streaming and creating online video content,” Gengmei vice president Wang Jun told the BBC.

Gengmei says it only works with licensed practitioners on its platform.

‘Prettiest to ugliest’

China’s tabloid culture can also be brutal. News publications often criticise celebrities for their appearance.

Earlier this year, a Shanghai art gallery promoted an exhibition that ranked images of women from “prettiest to ugliest”.

Lu Yufan, a Beijing-based photographer who is working on a book about cosmetic surgery, told the BBC that growing up, people would often be straightforward when it came her looks.

Her relatives would tell her that she looked like TV actresses – “not the pretty heroines but the funny side characters”, the 29-year-old recalled.

“When I was in middle school, boys also listed who they thought were the ugliest girls in class. They told me I was No. 5.”

Ms Lu, who has visited 30 cosmetic surgery clinics as part of her project, added that practitioners never held back when telling her how her face could be “improved”.

“They were so persuasive that I found it difficult to say no, except that I didn’t have the money for it,” she said.

For Ruxin, the eyelid operation is affordable, costing between $300 and $1,200.

But it’s just the first step.

“If this goes well, I’ll probably do more. Who doesn’t want to be prettier?”

bbc