A Chinese scientist’s attempt to produce the world’s first gene-edited babies immune to HIV has sparked heated controversy among the public and academics.

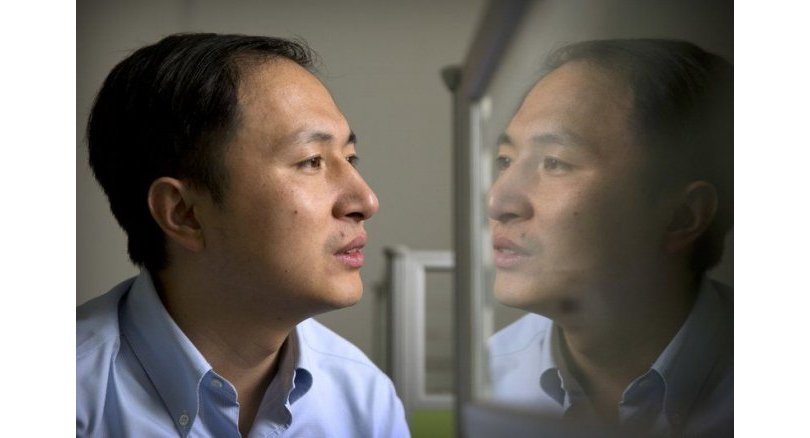

In an online video posted on Monday, He Jiankui, a biological researcher, announced that twin baby girls, Lulu and Nana, born healthy a few weeks ago, were conceived through in vitro fertilization and genetically edited for immunity to HIV infection.

“The mother started her pregnancy by regular IVF with one difference. Right after sending her husband’s sperm into her eggs, we also sent in a little bit of protein and instructions for gene surgery,” said He, from Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen, Guangdong province, speaking in the video. “Lulu and Nana were just a single cell when the surgery removed the doorway through which HIV enters to infect people.”

He, believed to be in Hong Kong to attend the Second International Summit on Human Genome Editing, a three-day conference due to open on Tuesday, could not be reached for comment on Monday. But his announcement sparked heated controversy over concerns over medical ethics and effectiveness.

The Associated Press reported on Monday that He sought and received approval for his project from the ethics committee of Shenzhen Harmonicare Women’s and Children’s Hospital, and an approval document from the hospital circulated online on Monday.

However, the Shenzhen commission said the hospital’s ethics committee was not valid because the hospital did not register the committee’s establishment with the commission as required.

The commission has started an ethics investigation and will release the results to the public, it said. The hospital would not comment on Monday.

Southern University of Science and Technology said on Monday that it was not aware of the research, as He did not report it to the school.

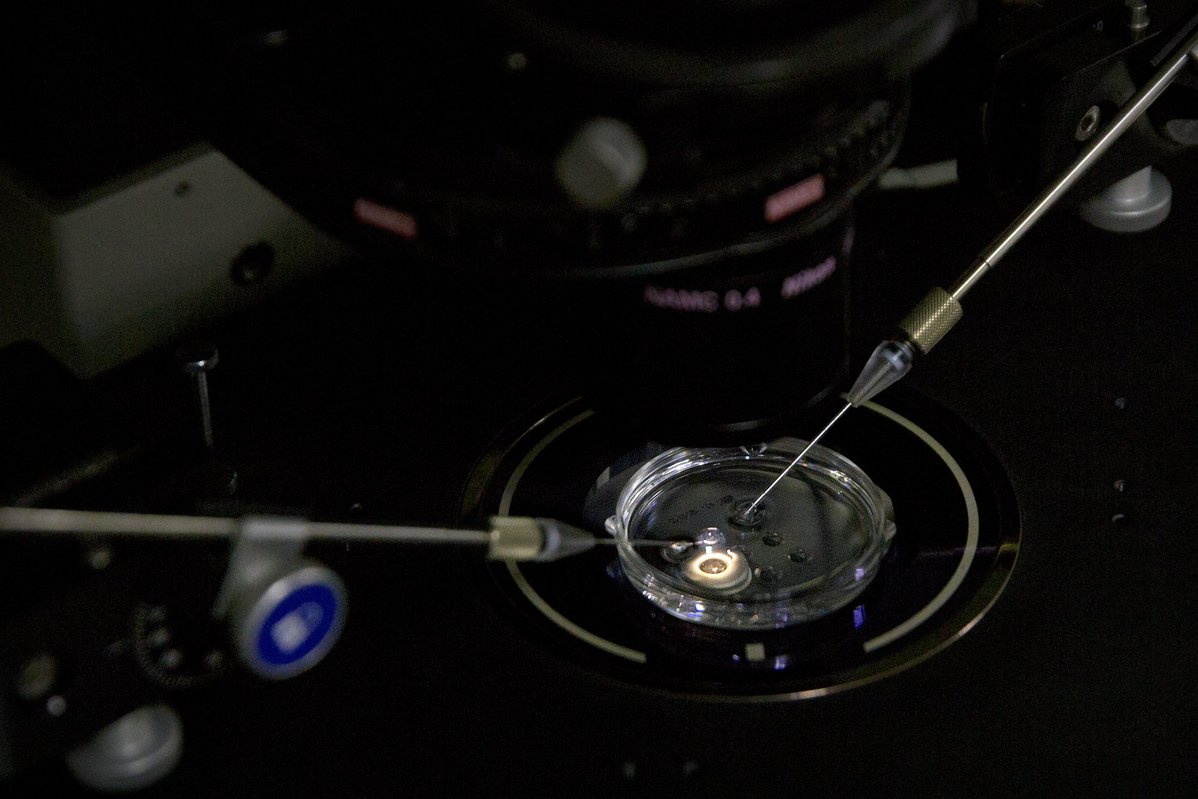

A worker places an embryo in a storage tube at a laboratory in Shenzhen. [Photo/Agencies]

The university said the academic council of its biology department, where He works as an associate professor, thinks that the research seriously violated academic ethics and rules. The university said it would immediately set up an independent investigation team for the matter.

A regulation released in 2016 by the former National Health and Family Planning Commission — now the National Health Commission — requires health institutions to establish ethics committees with authority over biological or medical research involving humans that would have to approve the research.

On Tuesday, the commission told its provincial branch in Guangdong to investigate the matter and handle it according to laws and regulations. The information should be made public in a timely way, it said in an official release.

Bai Hua, head of Baihualin, a nongovernmental organization that promotes the interests of people with HIV/AIDS, said on Monday that the parents of the twins were likely to have HIV.

He Jiankui spoke with Bai in April 2017, hoping to find people with HIV for the research, Bai said, adding that he spread the news and about 200 showed interest.

“Of the group infected with HIV, many have special conditions such as inability to conceive naturally, but the reality is that they cannot have babies through IVF in hospitals,” he said. “Many of them thought the research gave them a chance to have babies who do not have the risk of getting HIV.”

Mixed reactions

On Monday, more than 120 scholars from prestigious universities and institutes from China and abroad such as Tsinghua University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology strongly condemned the research in a signed statement, saying it lacks effective ethics oversight and amounts to human experiments.

In the statement published on weibo.com, they said any attempt to change human embryos with genetic editing and allow the birth of such babies entails a high degree of risk due to inaccuracies in existing editing technologies.

Wu Zunyou, chief epidemiologist at the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, said: “Genetic editing technology is far from mature and could have unforeseen consequences for the subjects.”

Some researchers are trying to use genetic editing technology to treat people infected with HIV, so the virus will not replicate and be transmitted to others, he said. “Animal experiments should be done to assess gains and risks for the subjects, before the possibility of doing this with humans.”

Some scientists in Hong Kong for the summit think it could induce serious problems for a person’s immune system, while others think people should not be overly scared because it would not affect the core genome.

Tsui Lap-chee, president of the Academy of Sciences of Hong Kong, said if one gene is edited, it will affect others that interact with it. And the whole genome, a collection of genes, may also be affected.

Robin Lovell-Badge, group leader and head of the Division of Stem Cell Biology and Developmental Genetics at the Francis Crick Institute, said “gene editing is not something to be scared about”, and he doesn’t think what He has done will affect a human’s core genome. Side effects may not be very serious as there are millions of healthy people with the exact same mutation.