A government minister has acknowledged that the cost of the rail strikes to the UK economy has exceeded £1 billion and that it would have been less expensive to resolve the pay and conditions issue with the unions months ago.

Huw Merriman, the rail minister, told members of the Commons transport select committee on Wednesday that the government had not “torpedoed” an agreement or “interfered in a negative manner,” but rather that the necessity for reform to working standards made the stalemate necessary.

Merriman referenced a study that said the cost of strikes to the wider economy from June to December was £700 million and claimed that strikes cost the UK rail industry £25 million on a weekday and £15 million a day at the weekends.

Ben Bradshaw, a Labour MP and committee member, questioned whether “almost a billion so far… would easily be enough money to have addressed this disagreement months ago, wouldn’t it?”

If you see it through that particular perspective, Merriman retorted, it has undoubtedly ended up costing more than it would have if it had been simply settled.

However, he added that in addition to the need for industry reform to bring in more cost-effective working procedures, the government also needed to “look at the total impact on the public sector pay accords.”

The adjustments, Merriman continued, “will actually pay for these pay accords and also make the railway more effective over time.”

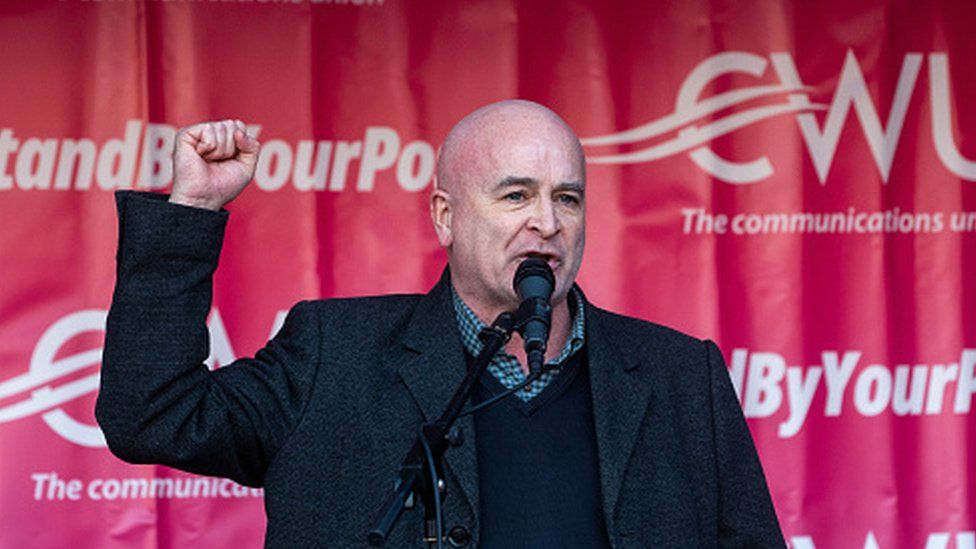

Merriman’s admission was pounced upon by unions and Labour, with RMT general secretary Mick Lynch contacting to business associations like the CBI and UK Hospitality to draw attention to his remarks.

The administration, according to Lynch, “confessed that extending the rail conflict was part of a deliberate strategy driven by the government’s aim to keep the wages of rail workers, nurses, ambulance drivers, and teachers low.

“That approach only caused collateral damage to the broader economy and the commercial interests that depended on pre-Christmas trading.”

The government is now “openly admit[ting] their posturing and inability to take responsibility has cost the taxpayer dear,” Labour shadow transport secretary Louise Haigh MP said.

While Merriman testified before the committee, Dame Bernadette Kelly, the permanent secretary at the Department for Transport (DFT), said: “You’re right about the extremely substantial economic impacts of interruption on the railway and we’re acutely cognizant of those.

The railway and the economy would suffer greatly in the long run if you settled at any costs, according to the logic of that argument.

Merriman expressed his “very hopeful” anticipation of a quick agreement with the RMT as discussions between the union and business this week continue. Further strikes by train drivers, sponsored by Aslef, were announced for February 1 and 3, although Merriman said he was “encouraged” by the union’s declaration that it was open to negotiations.

When asked whether the government was to blame for contentious last-minute restrictions on driver-only operation (DOO) of trains being inserted in a wage offer to the RMT, which the union said had “sabotaged” a deal in December, he did not immediately respond.

The minister insisted that no deal had been “torpedoed” by the administration. Merriman continued, “As a concept, DOO has always been active [in talks with unions],” and he claimed that the government desired more reform.

We haven’t turned away from the idea of DOO, he continued. We believe that if that technology can be implemented, we should implement it. Both its safety and effectiveness are improved.

He said that the DFT, the Treasury, and Downing Street were all involved in how the disagreement was handled.

According to Merriman, “the taxpayer, the government, and the money are all at danger.” “Employers are given a mandate about the financial envelope… However, it is up to the employers to negotiate the terms, not least of all the savings and efficiencies that can be returned. Of course, the government is involved in creating the broad framework in terms of how much… can be afforded.

I don’t think we interfered in a bad way, he continued. We were able to constructively intervene, in my opinion.

In response to a follow-up question regarding the “present mess” in northern train services, Merriman cited statistics from Transport for the North that claimed that poor connections were costing the Manchester economy £8 million per week.

“Really left its impact on me,” he remarked, referring to his trips to Bradford and Leeds. He continued, “It crushes my heart to see the performance so awful, because we’re letting people down.”