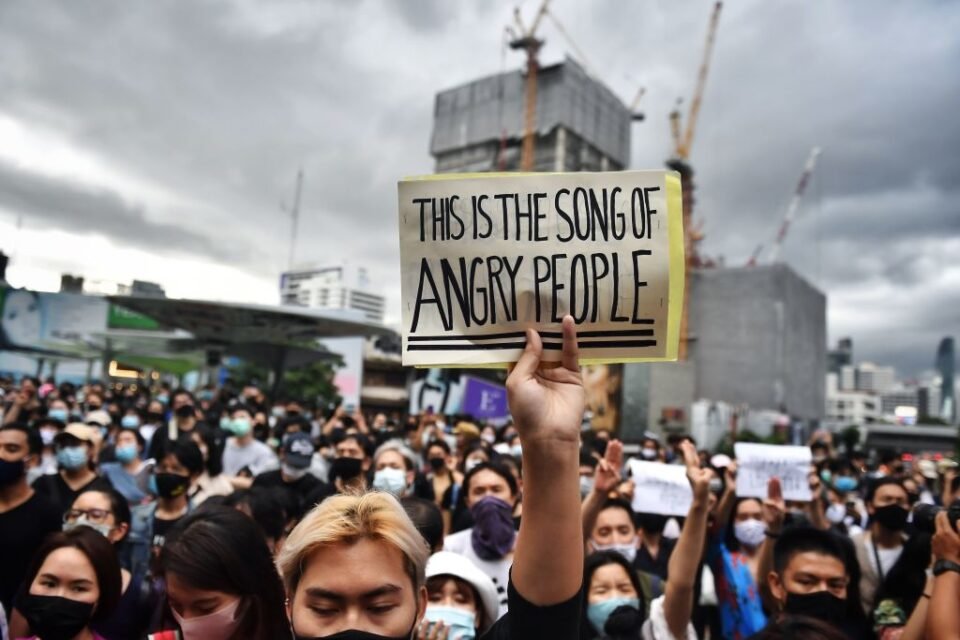

As Thailand’s youth continue to protest against the country’s establishment, the government faces double trouble, with an economy in free-fall.

At the heart of the protests are demands for new elections, change to the constitution, an end to intimidation of government critics and reform of the monarchy – a mix of grievances unlike what has emerged in previous popular uprisings.

Thailand’s economy, meanwhile, shrank by 12.2% in the second quarter as the coronavirus pandemic hit.

It was the biggest contraction in Southeast Asia’s second-largest economy since the 1998 Asian crisis and the worst result among the region’s big six economies (Indonesia, Philippines, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam).

The Thai economy was in deep trouble before the coronavirus hit, with export volumes down as a result of an ageing manufacturing sector and the US-China trade war.

Domestic demand was also softening due to slower-than-expected private investment on the back of weak exports and a slowdown in the residential sector.

GDP growth in 2019 was only 2.4%, the slowest in five years.

In August, the Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT) warned that foreign tourist arrivals in 2021 could be as low as 15% of 2019 levels under a worst-case scenario.

That would see international visitor numbers plunge from 39.8 million in 2019 to just 6.1 million, stripping 1.6 trillion baht (A$70 billion) from direct tourism revenues.

The pandemic-induced collapse of the tourism sector, which accounts for as much as 20% of GDP both directly and indirectly, has – along with sharply falling exports – created a crisis from which it will take years to recover.

The Thai government is forecasting GDP to contract by 8.5% in 2020, for now.

Behind the façade of Thailand’s image of a tropical paradise populated by happy, smiling people is a country trapped in time, dominated by intertwined elites in the monarchy, the military and the business aristocracy.

The tourist slump is hitting Thailand’s lowest paid, often rural domestic migrants, who have been forced to return to their farms.

As such, the situation will only accelerate the urgency for real change now being pushed for by Thailand’s youth.

In this way, the protests are slightly different to the regular upheavals in Thailand. In the past, these have been directed at a specific leader, political party, the military or some event. This time around, the country’s entire, inflexible system is on trial.

Behind the façade of Thailand’s image of a tropical paradise populated by happy, smiling people is a country trapped in time, dominated by intertwined elites in the monarchy, the military and the business aristocracy. It has some of the region’s highest income inequality.

Critics say Thailand has barely evolved from the 1932 military takeover, which saw the absolute monarchy reshaped under a constitution.

Since then, Thailand has suffered a relentless series of coups, enacted by the military whenever the winners of democratic elections fall out of favour with the establishment.

The military has worked in partnership with the monarchy, centred around a carefully nurtured cult of the King.

This arrangement worked well with King Bhumibol Adulyadej, the world’s longest-reigning monarch at his 2016 death.

It has begun to fall apart, however, under his son and successor, King Maha Vajiralongkorn, who is rarely in the country.

The impunity of wealthy business elites who control the country’s banks and major industries, often in financial partnership with the monarchy, was writ large in April this year with the dropping of 2012 dangerous driving–related murder charges against Vorayuth “Boss” Yoovidhya, heir to the Red Bull fortune, when a surprise “new witness” emerged after eight years.

The re-emergence of this scandal could not have come at a worse time for the government, as it has only fuelled student resentment.

The government has been forced into sharp reversal, ordering a fresh inquiry into the incident and the corruption surrounding it.

But the damage has already been done – not just in this case, but by the ruling military’s rampant tilting of the playing field since it took charge once more in a May 2014 coup d’état, which followed six months of increasingly violent street protests that claimed 33 lives and saw more than 200 injured.

The effect of the coup was to finally rid Thailand of the Shinawatra family, who have their support base in the poorer north of the country and who long dominated elections in the country, winning three general elections in the decade from 2001.

Now family patriarch Thaksin Shinawatra and his sister Yingluck, who both did stints as prime minister, remain in exile and are wanted in Thailand.

The first elections since the coup, held last year under a new military-drafted constitution that switched to an appointed rather than an elected Senate, saw the startling emergence – despite a renewed attempt at gerrymandering – of Thai Future Forward (TFF), who won surging support and pushed the Thaksinite “Red Shirt” parties down the list for the first time.

TFF garnered support both in Bangkok and more widely among younger people. Indeed, the protests began to take shape after TFF was banned by military-backed courts in February, but which were effectively put on hold at the onset of the coronavirus pandemic.

Far from recognising his country’s problem for what it is, the King – who spends most of his time with an extended entourage at his castle in southern Germany – has opted to stay away during the Covid-19 crisis. This has only confirmed resentment against the monarchy.

The situation initially led to a kind of stand-off, with the government uncertain of how to handle the student protests, but things appear to be sharpening with the arrest of key players in the movement.

Still, the worst nightmare for the government and its military backers could lay ahead. As the economy continues to falter, the youth protest movement could well find common cause with the Red Shirts, who represent the nation’s underclass.

Both groups are now sensing a future shorn of any opportunity. If they were to become a united force, there is no telling where things will lead. – lowyinstitute.org