You can easily imagine, I’m not the best placed to comment objectively on the decision of the court,” began the editorial in a council newsletter in the French town of Draveil.

The author of the article was the town’s mayor, a 63-year-old former minister who was recently found guilty of rape and sexual assault.

But despite his conviction, an appeal has allowed Georges Tron to continue to lead Draveil from his prison cell.

And many people are angry.

On Tuesday, a group of local activists held another protest in Draveil in the southern suburbs of Paris calling for Tron to be removed as mayor.

Members of the Not in Draveil or Anywhere Else (Nada) Collective dressed as chickens and accused local politicians of cowardice over the issue.

The case against Tron began over a decade ago, when he was forced to resign as a junior government minister following accusations of rape and sexual assault by two former employees.

He was acquitted at an earlier trial but in February this year he was given a five-year sentence, two years of which were suspended. He was also banned from holding public office for six years.

The problem, as local opposition politician François Damerval explains, is that Tron’s appeal against his conviction means he is presumed to be innocent until a final verdict is delivered – and he has therefore been able to continue his duties as mayor from behind bars.

France’s interior minister – who served as the mayor’s lawyer in his initial trial – has previously said that the government will not be able to remove him from office because of the ongoing appeal.

“The current system is problematic because it protects people who have been convicted of rape – even if there’s the presumption of innocence. But above all, he doesn’t have the moral capacity to lead the administration,” Mr Damerval told the BBC.

“Today on paper, he’s still the head of the [municipal] staff who was convicted of raping a member of staff.”

And it is the moral aspect of the case that Tron’s opponents are focussing on.

Gabrielle Boeri-Charles, another local politician, notes that the French cabinet has the power to revoke a mayor’s position under such circumstances.

“We consider that the loss of moral authority applies here because the acts for which he was convicted were committed in his position as mayor,” she says.

But gaining the support of other residents to remove Tron has been harder.

“We’re a small town of 30,000 people and when a mayor is here for 25 years he can implement a system in which he has a lot of personal power,” she says.

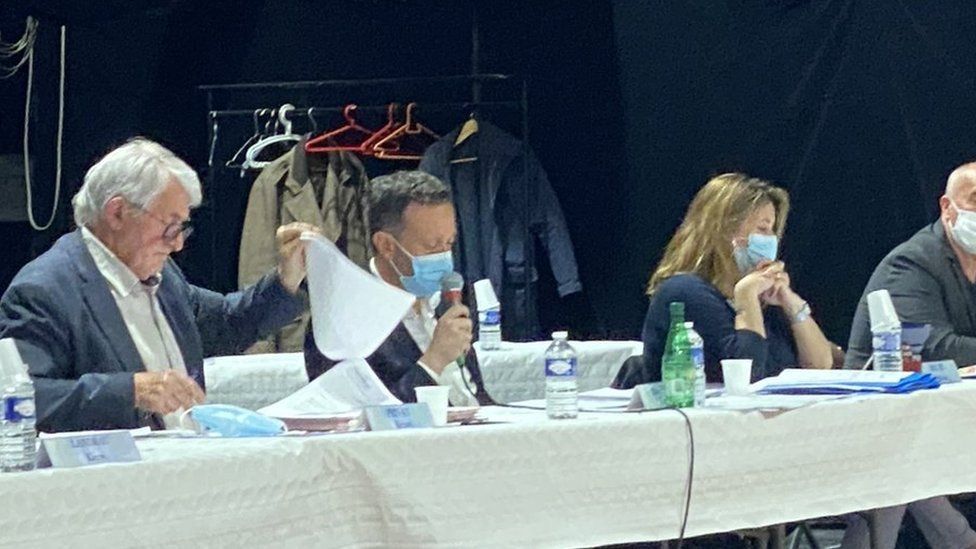

Since he was jailed in February, Tron has continued to preside over council meetings, with statements read out on his behalf in two sessions.

His deputy, Richard Privat, defended the mayor’s continued role in the town’s affairs, telling France Télévision in April: “Until there is evidence to the contrary, he is still mayor. No one has removed him from his post so he is still mayor.”

In a council meeting last month, the opposition put forward a motion calling for Tron to be removed but the mayor’s supporters left the room before a vote could take place. Ms Boeri-Charles says that online criticism has also been silenced.

“On the town’s Facebook page, they publish what he has written from prison but they refuse to publish what the opposition has to say. If you comment or criticise, it’s erased. And in a town, there’s not so much space to have a debate.

“The fact that he used his moral authority to act, and the continuing denial, silence and even support around him, is a collective failure,” adds Ms Boeri-Charles.

But the mayor’s opponents remain convinced he has to go.

At least 35,000 people have now signed an online petition demanding Tron’s resignation.

Raphaël Demonchy, a co-founder of Nada, says that in addition to holding protests, the group has spent time speaking to the town’s residents to explain why they believe the mayor should be removed:

“It’s not only about Draveil, it’s a more global situation about what the French Republic accepts from its elected officials.”

“In the post-Me Too era there is no more impunity for people who have committed sexual assaults,” agrees Mr Damerval. “And today, the fact that he can continue to rule from prison is an insult to women.”

bbc