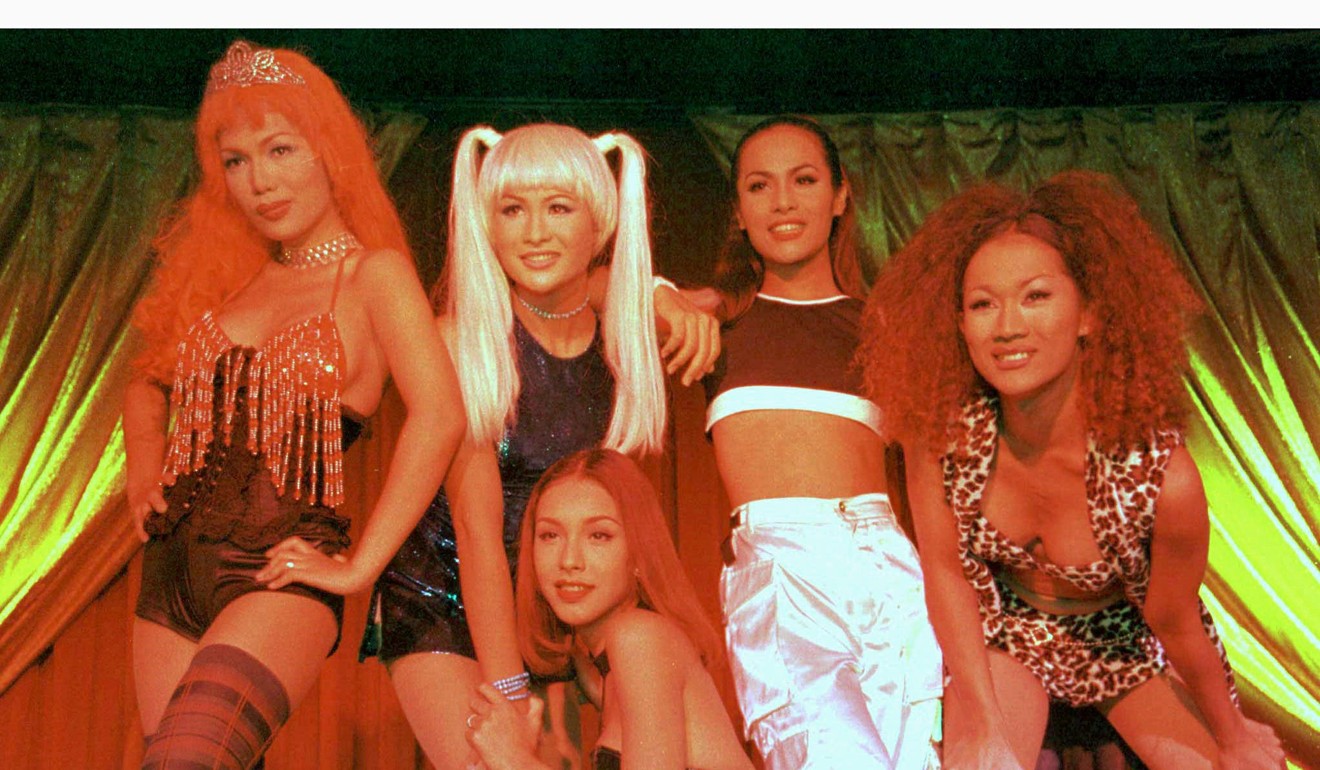

LADY BOYS: It is a country known to the world for its gay parties and transgender beauty pageants, a Land of Smiles that is welcoming to all.

But tell that to members of Thailand’s LGBTI (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex) community and you might receive a puzzled frown.

While Thailand is one of the most progressive countries in Asia regarding LGBTI rights, and its capital Bangkok often tops lists of gay-friendly tourist destinations, activists in the country say the gay community suffers not only from a lack of recognition, but from laws and a society that actively discriminate against them.

“Abroad you may think that in Thailand there is a very open space to express your gender identity if you are LGBTI. But in reality, it is very hard to express our identity because we don’t have the legal support,” says transgender activist Kath Khangpiboon.

Kath has suffered this discrimination at first hand. In 2015, she lost her teaching job at Thammasat University after issues surrounding her gender identity were brought up by the university committee.

She was informed she was “no longer suitable” to teach at the institution – Thailand’s second-oldest university – because of inappropriate behaviour on social media, referring to a post on Kath’s Instagram account featuring a photo of a penis-shaped tube of lipstick.

“Thammasat never said that my case was discrimination. They said that there was a problem with my behaviour on social media,” Kath recalls. “But to me it was related to my identity, to my natural behaviour. It was bias.”

According to Kath, the university had never previously shown concern over the social-media activities of its lecturers.

Thai law does little to protect the LGBTI community from discrimination. Same-sex marriages are not recognised and transgender people cannot change their gender on ID cards and other official documents.

Meanwhile, prejudice against the community means its members struggle to be accepted as lawyers, doctors or social workers and are instead confined to the entertainment industry, Kath says.

“Many organisations or companies don’t accept transgenders … because they are biased and they don’t see the abilities that transgender people have,” she says.

A World Bank report released in March found “discrimination [in Thailand] is prevalent when LGBTI people look for a job, access education and health care services, buy or rent properties, or seek legal protection”.

And a study by the International Labour Organisation found that many gay men and women hide their sexuality at the workplace, especially in the early stages of their career.

“While some lesbian and gay people reveal their sexual orientation at work, this depends on the workplace culture and the profession, as being gay, lesbian, or bisexual is perceived to damage credibility in leadership and high-status jobs,” the study concluded.

Kath says the “problem of Thai culture is that this is not a multicultural country. We don’t have people from other ethnic groups. This is why people lack understanding of diversity.”

Families often refuse to accept the lifestyle choices of their sons and daughters, Kath says, while LGBTI students often face problems at school or university, where teachers are not trained in protecting them from discrimination.

When Nada Chaiyajit completed her undergraduate studies at the University of Phayao, in northern Thailand, she was refused her college documents because she had submitted a photo in which she was dressed as a woman, while her ID card said she was a man.

“There is no legal protection in terms of recognition,” Nada says. “Even if you have sex reassignment surgery, your identity and your official documents will remain as you were born … and that sets barriers on our quality of life.”

Transgender students have long battled for equal rights in Thai universities.

In 2012, Thammasat University allowed for the first time a transgender student to dress as a woman for the graduation ceremony.

And some universities have in recent years allowed students to express their gender identities in official paperwork. However, even these institutions have required the students to request psychological help and obtain a certificate saying they have an identity disorder.

Pink Dot: Singapore’s rare gem for LGBT community shines brighter

Nada refused to toe the line and, rather than obtain such a certificate, filed a complaint against the university with the Committee on Consideration of Unfair Gender Discrimination, saying her freedom of expression had been impinged.

Indeed, Nada’s case offers some hope that attitudes, at least in education, are slowly changing. Both Nada and Kath won cases against their universities, setting important precedents. Kath had to be readmitted by Thammasat University and has been working as a lecturer since June, while Nada graduated in February 2017 without having to change her dress or claiming to have a mental disorder.

In other areas, there is cause for optimism, too. A 2015 poll found that almost 89 per cent of Thais would accept colleagues who were gay or lesbian; 80 per cent would not mind if a family member was LGBTI; and 60 per cent were in favour of legalising same-sex marriages.

In the same year as that poll, Thailand approved the Gender Equality Act, a milestone for the country as it outlaws gender-based discrimination. It was this law that led to the creation of the committee that ruled on Nada’s dispute with her university. However, the implementation of the law is progressing slowly, Kath says.

Where will Indonesia’s anti-gay hysteria end?

Meanwhile, the government is discussing a same-sex civil partnership law, which is expected to be passed before the end of the year. It is as yet unclear whether the law will include such basic rights as succession or adoption, though some activists have been critical, saying it will still not put such unions on par with heterosexual marriages.

“Thailand needs some time to move forward so it is a good start to legalise same-sex civil partnerships first,” says Nada, who took part in the drafting of the law. While it might be a landmark of sorts for the LGBTI community, she is clear more is needed.

“We are not starting from scratch. We already have some milestones that we have achieved but it doesn’t mean that our rights are guaranteed,” she says

“It is not enough.”