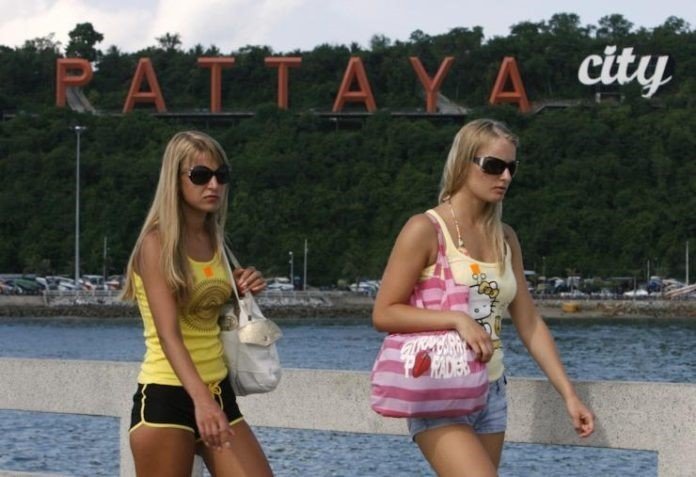

Is mass tourism a thing of the past in Thailand as the streets of the most popular tourist destinations are unnervingly quiet.

Along Chaweng’s Beach Road, a usually raucous party area, shuttered shops stretch into the distance.

Before the coronavirus pandemic, it was buzzing with traffic. Now, taxi drivers sit on the roadside, with little hope of finding customers.

Where bikini-clad sunseekers once browsed souvenir shops and drank at neon-lit bars, a lone street dog stretches on the pavement.

Elsewhere, swathes of Samui’s idyllic, sandy white beaches are almost entirely free of people.

About 40 million tourists flocked to Thailand last year, drawn by its spectacular coastlines, ornate temples and famous cuisine.

In 2020, the country will struggle to attract even a quarter of that number, according to the Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT).

Tourism ground to a halt in April, when Thailand imposed a ban on all incoming passenger flights. The country – which has so far managed to contain Covid-19, recording 3,255 cases and 58 deaths – is discussing travel bubbles with low-risk neighbouring countries, but no one knows when these might be established. Borders remain shut to almost all foreign tourists.

The travel sector has survived devastating crises before, including the 2004 tsunami, bird flu and Sars outbreaks.

But the impact of the coronavirus pandemic is beyond comparison, says Tanes Petsuwan, deputy governor for marketing communication at the TAT.

During previous crises, revenue dropped by around a fifth, he said. This year, the coronavirus pandemic is expected to cause an 80% fall in revenues. “It’s a huge impact,” he said.

To make matters worse, Thailand’s economy has become even more reliant on tourism, accounting for almost 20% of GDP, according to Tanes. About 4.4 million people are employed across the industry – in transport, travel agencies, restaurants and hotels.

In Samui, many have gone for months without work. Before coronavirus, Jarunee Kasorn, who works in a local massage parlour in Chaweng, says her colleagues would welcome up to 90 clients a day.

They’re one of the few businesses to reopen on Beach Road, but a whole day can go by without a single customer. “If there are no tourists, then there’s no business,” she said.

Most of the shop’s 20 staff have left the island altogether, and returned to their family homes elsewhere in Thailand.

Though modest social assistance payments were offered to workers during lockdown, this is no longer available.

“Many people say we won’t die from Covid, but we will die because we are not able to eat,” says Ta Sasiwinom, who has just reopened her stall at an outdoor market in Fishermen’s Village, known as the walking street. The past few months have been a struggle for her and her two daughters. “We cook more cheaply – eating egg and rice, rice and egg,” she says.

Parts of the market, and the nearby beach, have begun to return to life. There are groups of visitors and locals peering at the discounted stalls, but it is still nowhere near as busy as it would usually be.

Among those shopping are tourists stuck abroad, foreign residents living in Thailand, and Thais – who the government has encouraged to travel domestically through a stimulus package that offers subsidised hotel bookings.

The scheme, and a looming long weekend, has provided a welcome boost, says Lloyd Maraville, general manager of Nora Buri resort and spa.

Of the hotel’s 144 rooms, about 100 are empty, though this will fall to 85 over the holiday.

Government measures, he adds, “might sustain hotels for a while but it will not be a long-term [solution].” Rooms have been booked at far below the usual rates. “Profit is out of the question at this moment, we just want to maintain the resort,” he says.

Tanes believes that when tourism is able to begin again, the industry will be altered completely.

He hopes for positive change. “I think this is a good time for Thailand to upskill the human resources of the industry to move Thailand [away] from [being an] overcrowded tourist destination,” he says. Mass tourism, and the dependence on large tour groups, he argues, will be a thing of the past.

In Samui, businesses are focused on survival for now. Just last month it was announced that nearly 100 local hotel owners had been forced to sell. Many more remain shut indefinitely.

“I’ve lived here for 20 years and I’m shocked, I never thought it could be like this,” says Rattanaporn Chadakarn, who runs a stall at the walking street.

No one knows how long the crisis will last. For now, she adds, everyone is just waiting for the skies to reopen.