Fast trains from Laos to China offer connections, albeit at a price and with enormous promises but uneven development.

As people wait for the reopening of the border to increase income and investment, “special economic zones” are thriving as an indication of expanding Chinese influence in Laos.

Thousands of people have been uprooted, though, and woods have been bulldozed to make way for a new railroad line despite visible evidence of progress.

Boonxay pauses to consider what connection means to a country that has been cut off for years under a rail bridge that crosses his sleepy northern Laos hamlet.

The father of five eventually remarks, “I see prosperity when I look at the train.” Do you realize that some of the elderly residents of this building have never even visited the capital in their entire lives? Now they are traveling for the first time.

The $6 billion track hinges Laos’ fate—one of Asia’s poorest nations—on China, the second-largest economy in the world.

It is essential to the communist leadership of Laos’ intentions to quickly lift its seven million people out of poverty and integrate Southeast Asia’s sole landlocked nation into the global economy.

The ambitious high-speed railway that China is building through the tough terrain of Laos is the first step toward lassoing the Mekong River and eventually the Malay Peninsula into the orbit of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative. It is a 422 kilometer line.

However, it seems that there has been inconsistent growth throughout Laos.

As “special economic zones” along the railway start to take shape and Chinese investors infuse vitality and a new tier of economic hierarchy into far-off, forgotten communities, land prices — and farmer incomes — are soaring.

Along darkly lit roadside, Hutong-style pubs and Xiaomi phone stores serve as beacons of wealth, and WeChat’s translation feature serves as the medium of exchange between Chinese pioneers and their Laos business partners or romantic interests.

Tens of thousands of people were displaced in order to develop the railway, power plants, mines, and dams that are guiding Laos toward its future.

Despite government pledges to protect them, one of Southeast Asia’s most biodiverse countries’ forests bear the scars of change: large-scale fruit, rubber, and corn plantations lap up the sides of formerly uninhabited hills, and deep, red earth gouges mark where infrastructure is eating into old forests.

Ethnic groups at the bottom of the economic food chain claim they are being priced out of prime land and are instead pursuing the forest further uphill with their “slash and burn” farming. This small country that has bet everything on China has undergone rapid change thanks to high-speed rail.

Along the Belt and Road Initiative of President Xi Jinping, Chinese frontiersman Zheng succeeds. With a large, friendly smile, a faded picture of Jay Z on the wall, and baijiu bottles stacked along the shelf of the bar behind him, he tells his story in a border village in Laos:

“I drove a truck for two years… This Week in Asia interviewed the 44-year-old Dalian resident in Boten. “I saved up and now I have this bar,” he said. “All we have to do is wait for the border to open. When it does, this place will blow up.”

Boten, a “special economic zone,” rises impossibly above; 30-story structures and mostly completed condos are waiting for Beijing’s approval to reopen the border so that contractors, investors, and day-trippers can return.

China continues to maintain strict border security against the coronavirus by implementing “closed loop” testing for truckers transporting fruit from Laos and seafood from Thailand. However, according to government figures, Laos sent commodities worth US$691 million to China along the train line in the year that ended in August. This was crucial activity for a faltering economy.

In June, the ratings agency Moody’s downgraded Laos’ outlook from stable to “negative,” citing analysts’ predictions of an impending default on billions of dollars’ worth of debt, the majority of which is held by China, as well as the country’s punishingly high inflation rate of about 35%.

Analysts believe that the railway could provide some measure of redemption.

The World Bank predicts that if investments are made in border technology, logistics, human capital, and tourism, the line could increase Laos’ income “by up to 21% over the long run.”

China is also eager to highlight the benefits of a project that it has divided 70–30 with its neighbor to the south.

According to Yunnan government statistics released this month, the train has carried 7.5 million passengers and nearly nine million metric tonnes of freight since its inaugural journey in December 2021.

The “special economic zones” (or SEZs), which are essentially commercial tax havens on long-term leases, are already spreading from Boten to Vientiane, close to the Thai border, but for the time being Boten is only a thumbnail on the belt and road network, a sampling of what is to come. If everything goes according to plan, they should attract investments worth billions of dollars from China, Vietnam, Thailand, and Korea. However, connection has a price.

Approximately 680,000 hectares of forest cover have vanished during the past 15 years, according to Bounyadeth Phouangmala, country director for The Center for People and Forests (RECOFTC).

His organization assists women and marginalized ethnic groups in Laos in developing economies from their common resources by encouraging locals to use their woods in a sustainable manner. According to Bounyadeth, “the extension of agricultural land for cash crops, shifting cultivation, and infrastructural development… electricity, mining, road, and rail construction” are the main causes of deforestation.

Global Forest Watch data shows that Laos lost 318,000 hectares of natural forest in just 2021. On their journey to China, high-speed trains now whiz past the impoverished northern Laos provinces of Luang Prabang, Oudomxay, and Luang Namtha, where little under one-third of that vanished.

According to the conservation advocacy group, four million hectares of trees have been cut down since 2000, the majority of them being primary forest, which consumes the most carbon dioxide.

To enable trucks to reach a new Chinese mining concession, a road is being constructed in the isolated hills of Oudomxay province in Laos.

Thousands of employees and businesspeople are brought to formerly pristine areas by concessions for mining and dams, and the railroad is now a major route to China.

That is bringing fresh eyes to an ancient resource: priceless wood.

We are a nation of supply and demand, so it’s not that difficult to find it, said a Laos wood broker who connects Chinese buyers with suppliers of the expensive rosewood and Makha hardwood used in furniture and elaborate decorations

“You can obtain whatever you want: various varieties and grades, whatever the Chinese buyers are looking for.”

In a ground-breaking Forestry Law from 2019, the Laos government outlawed unlawful logging and export, particularly of rare woods. It plans to build four million hectares of conservation areas in the future years, or nearly the same amount that has been cut down since 2000, with the goal of promoting “green growth.

A sustainable use of “limited natural resources for optimum advantage, especially forest resources” was required under the forestry law.

However, a government goal of reaching 70% forest cover has been postponed until 2035 and is still awaiting formal approval.

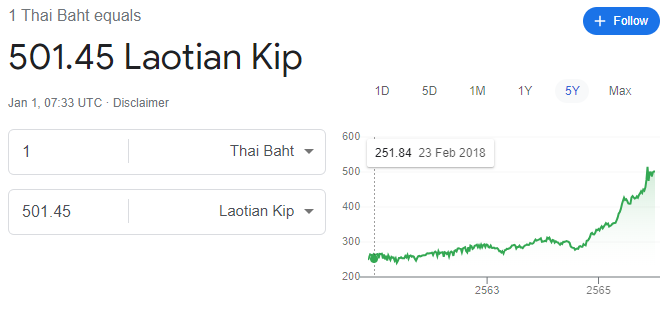

There has been significant Thai Interest in the region quite simply because of the exchange rate of late!