In rural Cambodia, dozens of people have died in recent months after drinking toxic home-brewed alcohol. In the village of Thnong in Kampot province, a bad batch consumed at a funeral left tragedy in its wake.

Prom Vannak, 50, would rarely go a day without at least a few glasses of rice wine, especially after a serious motorcycle accident that left him unable to work as a fisherman.

So when his uncle Muth – who was also a big drinker – passed away in May, there was no doubt that the funeral would be spent drinking and reminiscing with friends and family in the village.

Vannak started drinking that morning and fell asleep early in the evening. When he woke up the following day, he told his wife he didn’t feel right.

“He told me he felt very tired and that when he drank the wine it made his eyes feel drowsy,” Hun Pheap recalled.

Pheap didn’t think too much of it, and returned for the second day of the funeral. Vannak stayed at home to sleep off what they thought was just a bad hangover.

But by that evening, Vannak had started shaking and violently throwing up. Pheap tried to persuade her husband to go to the local hospital but he refused, saying he just needed rest. The following morning he was dead.

“He opened his mouth to try to send a message to his mother and children,” Pheap said. “His tears were falling, he was passing away. He could only open his mouth but could not talk.”

Vannak was one of eight people who died after drinking at his uncle’s funeral. More than 50 others were hospitalised. And two people from the village died after drinking from the same batch.

Hun Vy lost two relatives and was rushed to hospital after drinking the toxic brew. “After I drank it, I felt dizzy, started vomiting and my hands and feet became weak,” he said. “I could have died.”

The mass poisoning was one of three cases in Cambodia in less than a month, resulting in at least 30 deaths. Thirteen people died in Pursat province at the start of June, and at least 12 people lost their lives in Kandal on 10 May.

Tests on the funeral batch showed that efforts to raise the drink’s potency had resulted in deadly levels of methanol. Methanol poisoning is not a new problem in rural Cambodia – homemade alcoholic brews are popular at wedding parties, village festivals, and funerals as a cheap alternative to commercially produced beer and spirits.

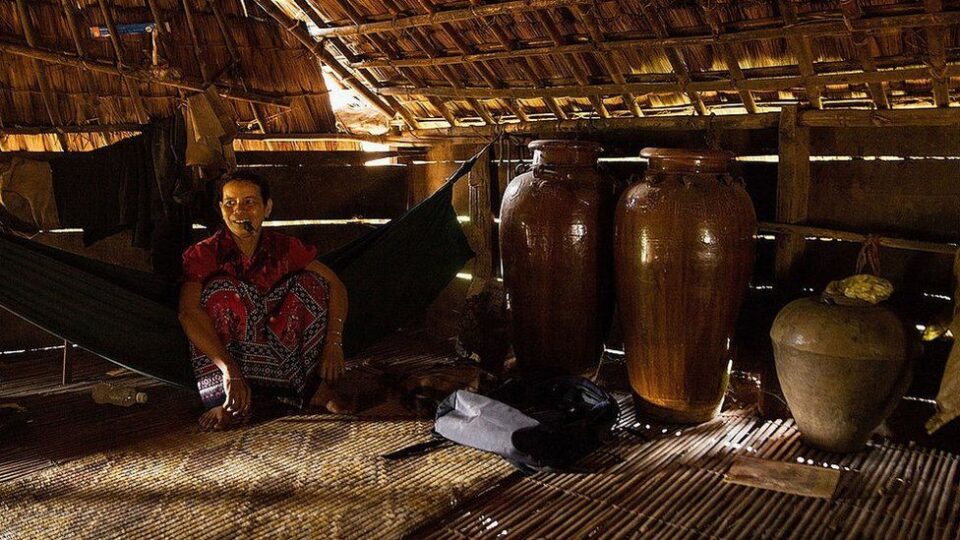

“Since the mid-1990s, when I started working in Cambodia, the situation has been pretty constant, with home distillers operating ramshackle stills inside their houses or shops, and selling this home-produced rice whiskey to their neighbours,” said Jonathan Padwe, an anthropologist who has worked in the country.

Most villages in Cambodia have at least one – often two or three – of these stills, but there are no legal controls, inspections or quality controls, Mr Padwe said.

Methanol is a kind of alcohol commonly used for various industrial purposes, including as a solvent in ink, dyes and varnishes.

Since it is cheaper to produce than ethanol – the only type of alcohol which is safe to drink – it is often added to increase the content in alcoholic drinks for profit reasons, especially in low-income countries like Cambodia.

Since the recent spate of deaths, Cambodian authorities have been attempting to show they are taking the problem seriously.

At least 15 rice wine brewers and sellers have been arrested, Cambodian police say, while the health ministry has called for people to avoid drinking contaminated alcohol.

In Pursat, officials have banned the production and sale of rice and herbal wines.

The district where Thnong village is situated has temporarily banned the production, import and export, and distribution of rice wine.

But Dr Knut Erik Hovda, a global expert in methanol poisoning, based at Oslo University, said that education on the dangers of bootleg booze was more important than going after the sellers.

“Of course, if I was the Cambodian government I wouldn’t let the people keep selling that toxic alcohol, but I wouldn’t put my focus on it either,” Dr Hovda said.

“I would rather put my focus on educating people and the healthcare providers on how to handle it when it happens. It has been happening for the last 100 to 150 years, and it’s going to keep on happening.”

Shutting down bootleg brewers would only result in new brewers cropping up, Dr Hovda said. Instead it was paramount to trace the source of bad alcohol, he said.

He said the health ministry had made some headway in implementing programmes to better identify and prevent methanol poisoning, but progress had been hampered by the Covid-19 pandemic.

The health ministry declined to comment for this story.

In Thnong village, the atmosphere has not been the same in the village since the day of Muth’s funeral. Many are mourning their losses.

Police came to question a woman who had sold rice wine in the village for decades, after locals said they had purchased some of the alcohol from her. But she was not arrested.

The woman, who gave her name only as Kolap, and others in the village believe the ghosts of those who passed away are still present.

“I am scared of the ghosts because on that day there were many people who died and it frightens me,” she said. “They make noise in my house and I can’t sleep.”

Hun Pheap has similar fears, even after calling the local achar – a lay individual who leads traditional ceremonies – to lay her husband’s spirit to rest in a chanting ritual. She says she misses her husband and sometimes imagines they are sitting next to each other watching the youngsters in the village play volleyball.

She welcomed the news that local rice wine sellers had been shut down, but said it was too little, too late.

“Without my husband, my life is like a kite flying without a rope,” she said. “I am angry, but what can I do?”

bbc