This academic thinks that the tales of Hiroshima’s living hibakushas would serve as a lasting warning against the horrors of nuclear annihilation as the city hosts the G7 conference.

The annual Group of Seven (G7) leader’s summit, which brings together seven of the richest nations in the world, will be held in Hiroshima, the first city to be completely destroyed by a nuclear bomb. This event will put the current global challenges in stark contrast. Importantly, leaders will have a unique chance to interact in person with survivors who still desire to share their tales with the world.

Hiroshima, which was forever etched into the collective unconscious, has come to represent tenacity in the face of nuclear annihilation. The hibakushas, as the survivors of the atomic bomb are known, also reside there in huge numbers. Hibakushas are thought to number 118,935 in Japan, with 39,590 of them still residing in Hiroshima.Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida is to thank for the city’s hosting of the G7 summit. Being a Hiroshima native, he has never shied away from highlighting the importance of his hometown.

As the foreign minister, he assisted in organizing Barack Obama’s 2016 visit to Hiroshima, where he met with survivors. Kishida presented his Hiroshima action plan, which aims to improve and sustain the non-proliferation pact of 1970, after announcing this year’s G7 in Hiroshima.

Kishida also promised to invite world leaders to Hiroshima and Nagasaki so they might witness the terrible effects of utilizing nuclear bombs.

In my research, I examine how different generations can redefine survivor accounts. The third generation, or hibaku sansei in Japanese, the grandchildren of survivors, are the ones I am currently interviewing.The lack of transparency around the history of the atomic bombings greatly offends survivors, who are sometimes unwilling to share their experiences. I think it’s crucial to repeatedly interview people in order to learn about their stories, silences, and other factors by utilizing their viewpoints and experiences.

PEACE AND WAR

The conflict in Ukraine, tensions between China and Taiwan, and an accelerated global arms race are just a few of the issues that are intensifying at the time the G7 leaders are gathering.

With the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki marking the end of its terrible defeat in 1945, Japan withdrew from international affairs after the Second World War. In addition to killing hundreds of thousands of people, this horrifying crime also left countless numbers of survivors with illnesses that have been passed on to their offspring.

Therefore, it is encouraging to hear a Japanese leader say that the G7 conference should, in a time of war, be primarily focused on peace.

Hiroshima currently features lovely parks, memorials, and museums that display the bomb’s components and human impact seventy-eight years after it almost ceased to exist. At the time, it was anticipated that the city would experience little growth for many years.

After the explosion, it was understandable that many survivors left the area or immigrated, but some persevered under extraordinarily trying conditions to conduct crucial study into how the atomic bombs affected the city’s environment and geology.

Some calmly went about performing medical research and treating survivors, leading to the care homes and hospitals that now look after thousands of elderly hibakushas. Others created heartbreaking works of art that expressed personal torments.

In addition to wanting to assist their fellow people, they also hoped that by working hard, the globe would one day visit the revitalized metropolis. To grant their wish, Fumio Kishida, a Hiroshima native, had to ascend to the position of prime minister.

THE STORY OF SURVIVING TO TELL

At great personal sacrifice, the survivors rebuilt the city and helped keep the memories of the atomic blasts alive for future generations.

Keiko Ogura, now 86 years old, was barely eight years old and living at home in a Hiroshima suburb when she was exposed to radiation, including from the deadly “black rain” that poured from the mushroom cloud on August 6, 1945. Ogura is a city official storyteller.

She has tirelessly carried on her husband Kaoru Ogura’s legacy as one of the founding directors of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum by sharing the experiences of the hibakusha with the rest of the world.She admitted that revealing her own tale of being exposed to the atomic bomb had caused her a great deal of worry during our interview for my study. Hibakushas were raised in a society that was biased and repressive.

Previous

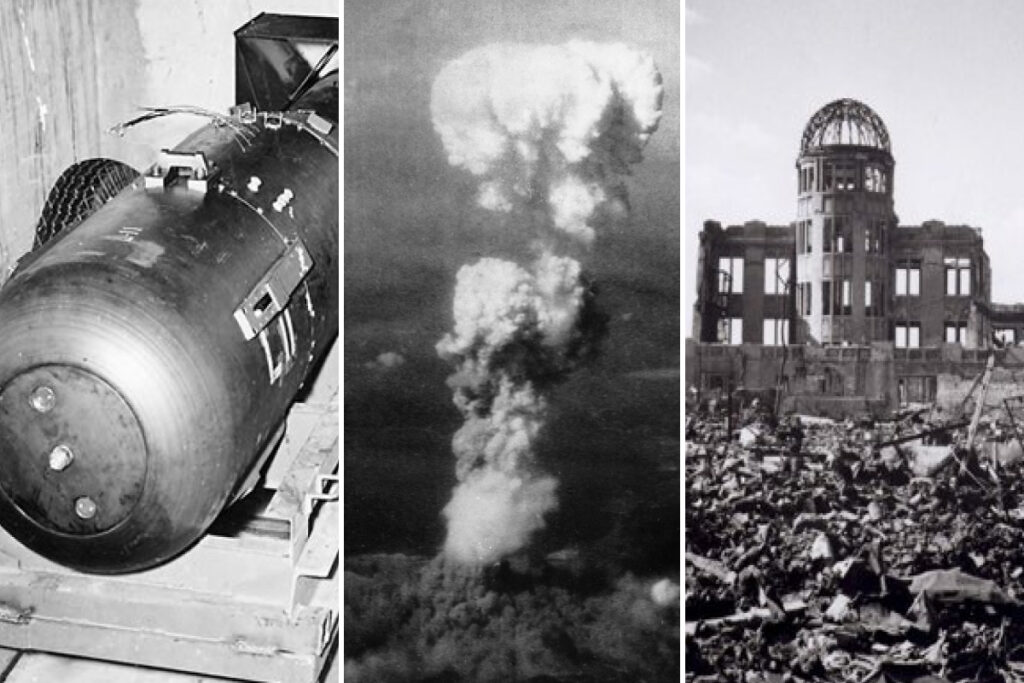

The Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall after the atomic attack is depicted in a September 1945 file photo. (Image: AFP)

The US air force unleashed an atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, marking the beginning of the nuclear age. (Photo: AFP/HIROSHIMA PEACE MEMORIAL MUSEUM)

The Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall after the atomic attack is depicted in a September 1945 file photo. (Image: AFP)

The US air force unleashed an atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, marking the beginning of the nuclear age. (Photo: AFP/HIROSHIMA PEACE MEMORIAL MUSEUM)

The Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall after the atomic attack is depicted in a September 1945 file photo. (Image: AFP)

Next1 2

Following the explosion, the Japanese military government and the US occupation both worked to have any reference of the seismic event removed while downplaying the deadly consequences of the bomb on human life and stifling survivor accounts.

“Can you imagine if you had to watch those you care about undergo excruciating suffering,” asked Kyoko Gibson, 75, a Hiroshima native who now resides in the UK. When Japan capitulated on August 15, 1945, the hibakushas were resolved that they would not be treated as mere victims and willingly agreed to become the tragic collateral damage.

Nobel Prize-winning novelist Kenzaburo Oe wrote about how a conversation with a hibakusha for his 1965 book Hiroshima Notes transformed his life for the better in a series of autobiographical works. He continued to fight for their cause throughout his life, insisting that the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki had taught humanity a valuable lesson about the importance of introspection.

The G7 leaders may discover, emotionally and logically, that approving Kishida’s action plan and the accompanying agreement on the policy of no-first-use is the only moral course of action if they hear the heartbreaking testimonies of Hiroshima survivors.

This might make the room for respectful discourse across differences that is much needed. Will they seize this chance?

The peril to all of us, as stated by physicist Albert Einstein and philosopher Bertrand Russell in 1955, is still likely the greatest menace to world peace today: the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. The tales of Hiroshima’s hibakushas ought to serve as a constant caution against this terrible act of human stupidity.