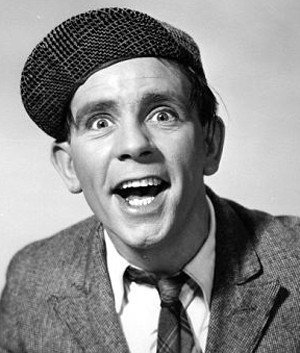

Remembering Sir Norman Wisdom who passed away 11 Years ago today.

Knockabout clown in the music hall tradition who found enormous success in the cinema.

What are your memories?

Engulfed by helpless, gurgling mirth, Norman Wisdom would subside to the ground as if suddenly rendered boneless: it needed someone only to look at him to make him fall down.

Often, the person looking at him – and sternly, at that – was Jerry Desmonde, doyen of variety straight men, who represented the figure of authority in many of Wisdom’s hugely successful film farces of the 1950s and 1960s.Wisdom, who has died aged 95, was almost the last in a great tradition of knockabout, slapstick clowns, a performer who relied less on words than on an acrobatic physical dexterity to gain his laughs.

He was usually derided or ignored by the serious critics, but in his day he was adored by the public, and because of its nature his craft travelled well – he was immensely popular in many other countries, including Albania, where he was known as Pitkin, after the character he played in many of his films.

If he had a penchant for tearjerking ballads and crude pathos, this merely reinforces a feeling that his career was somehow spent out of its correct time.

He properly belonged to the earlier era of the music halls, an appropriate setting for his combination of agile body-comedy and sometimes mawkish sentimentality.

He was born in Marylebone, London, in conditions of desperate poverty. As a boy he often had to walk to school barefoot, and when his mother left the family home he and his brother were disowned by their father.

He was placed in a children’s home, from which he ran away when he was 11, and he started work as an errand boy at a grocer’s when he was 13.

When the second world war broke out, Wisdom joined the army and served in India.

He made his first appearance as an entertainer with a comedy boxing routine at an army concert, and developed his musical skills when he joined the Royal Corps of Signals as a bandsman in 1943.

After the war his variety debut came at the old Collins Music Hall on Islington Green, north London, in 1945, and he started touring Britain in pantomime and summer shows.

In 1948 he made his first West End appearance, on a variety bill at the London Casino, and became famous virtually overnight.

“A star is born!” announced the Daily Mail, and the following week Wisdom went straight to the top of the bill at the Golders Green Hippodrome, north London.

His next date was a summer show with the magician David Nixon, and for this appearance he meticulously worked out the characterisation for which he became famous: variously known as Norman or The Gump or Pitkin – an enthusiastic, puppyish little man with a too-tight tweed jacket and crooked cap.

Attired as such, and complete with the later familiar jerky gait and propensity for sudden collapses, he played a volunteer who came out of the audience to help – and, of course, reduce to a shambles – Nixon’s magic act.

After further successes in the West End and elsewhere, he made his first Royal Variety Performance appearance in 1952, and his film debut, Trouble in Store, the year after.

He also topped what was then known as the hit parade with a song from the film, Don’t Laugh at Me ‘Cos I’m a Fool, the title conveying his tendencies towards toe-curling pathos.

It was surely this meld of slapstick and tearfulness that prompted the grand master of the genre, Charlie Chaplin, to embrace Wisdom as his “favourite clown”.

A string of money-making films followed, including One Good Turn (1954), The Square Peg (1958) and The Bulldog Breed (1960).

As well as his nemesis, the supercilious Desmonde, these films often featured another authority figure in Edward Chapman as his boss, the more down-to-earth Mr Grimsdale.

As with those of George Formby and Old Mother Riley before him, his films were much more popular with the public than with the critics, whose comments generally ran along the lines of: “Norman Wisdom up to his usual predictable antics.”Less notable, in commercial terms, were his stage appearances.

Where’s Charley? at the Palace, London, in 1958 went down quite well, but The Roar of the Greasepaint – the Smell of the Crowd was a tremendous flop that never reached London after a Manchester tryout in 1963.Wisdom went to Broadway for the Tony-nominated musical comedy Walking Happy in 1966, and then to Hollywood.

He brought depth to his portrayal of a vaudeville star in The Night They Raided Minsky’s (1968), which also featured Jason Robards, Britt Ekland and Bert Lahr.

“So easily does Wisdom dominate his many scenes, other cast members suffer by comparison,” wrote Variety.

It became apparent that Wisdom was valiantly trying to change his image.

This was vital for professional survival.

Comedians whose stock-in-trade is childlike innocence – even those as great as Stan Laurel and Harry Langdon – or adolescent awkwardness, such as Jerry Lewis, generally encounter career problems in middle age.

The clowning that seemed so enchanting becomes almost sinister when the face gets jowly and the hair recedes.

Wisdom’s way of dealing with it – though it now seems brave – was utterly disastrous.

In 1969 he made a fairly sophisticated sex comedy, What’s Good for the Goose, in which he did a bedroom scene with Sally Geeson.

His public was not ready for the little Gump in bed with a woman, and Wisdom’s career as a top film comedian was over.

He continued to tour his one-man stage show very successfully, and had one startling dramatic success in 1981 when he appeared in Going Gently on BBC2.

In this harrowing play, set in the cancer ward of a London hospital, he portrayed a retired salesman unable to come to terms with terminal illness.

For once the pathos was unforced, and Wisdom triumphed in a difficult role, winning a Bafta award.

He also tried television in a number of sitcoms, but the medium was not his forte.

While he toured South Africa and Australia with some success, his appearances in Britain became more infrequent.

Extremely wealthy, he spent much of the 1980s in seclusion on the Isle of Man, rather than do the usual round of TV game and chat shows, though he made something of a return to prominence in the 1990s, looking hale and trim.

He appeared as Billy Ingleton in several episodes of Last of the Summer Wine between 1995 and 2004, and in 2004 again even turned up in Coronation Street as pensioner Ernie Crabb.

In 1992 he had played a retired burglar in a film thriller, Double X, which sank almost without trace, but, more tellingly, the following year he was the subject of a South Bank Show in which he explained the secrets of pratfalls, backward tumbles and stair-falls.

Those of us who had always admired him felt privileged to see a master of his craft allowing a glimpse of the astonishing skill and body control that had gone into something that seemed so effortless and artless.

Wisdom was knighted in 2000, an honor many felt long overdue considering his contribution to the British film industry: at the height of his fame his films made more money than the James Bond series.

He announced his retirement from show business on his 90th birthday, in 2005.

Two years later he went into residential care at a nursing home on the Isle of Man, and in early 2008 a poignant BBC television documentary portrayed a clown in extreme old age – still chirpy, but obviously suffering from dementia.

It was said that his memory loss was so severe that he no longer recognised himself in his own films.

He was divorced from his second wife, the former dancer Freda Simpson, in 1969, and is survived by their children, Nicholas and Jacqueline.•

Norman Wisdom, comedian and actor, born 4 February 1915; died 4 October 2010