The recent mass shooting in Nong Bua Lam Phu province was the deadliest in Thailand’s history. The tragedy revealed even more shocking statistics, particularly the country’s high ranking for gun violence and possession. It also restarted the conversation on gun laws.

Gun violence trend

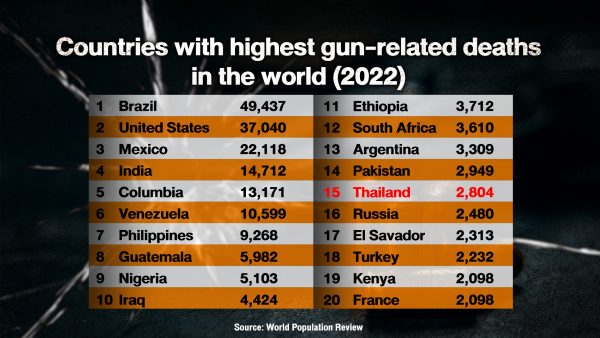

Thailand is currently ranked 15th among countries with the highest number of gun-related deaths, and ranked 2nd in Southeast Asia, according to the World Population Review website.

Countries with the highest number of gun-related deaths are Brazil, the United States, Mexico, India and Columbia, while the Philippines has the highest number of deaths in the ASEAN region.

While it seems like gun violence and mass shootings are becoming more frequent, Southeast Asia, in fact, has less gun violence than other continents. Gun violence is much higher in the Americas.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) also sees a downward trend in gun violence and homicides in Southeast Asia. Therefore, recent mass shootings in Thailand, both in Nong Bua Lam Phu and Nakhon Ratchasima in 2020, are considered quite “unique” for the region.

“In Southeast Asia and in Thailand, despite being appalling and tragic, we’re not at levels that we can see in other continents,” said Julien Garsany, the Deputy Regional Representative for Southeast Asia and the Pacific of the UNODC.

Availability

As to why Thailand has the highest gun possession in ASEAN countries, Julien explains that it’s mainly because of theavailability of guns, both legal and illegal. Such weapons can also be easily purchased on the black market and online.

According to the Small Arms Survey (SAS) in 2017, Thailand has the highest number of guns in the possession of private individuals among ASEAN member countries.

Among a total of 10,342,000 guns recorded, 6,221,180 were legally registered and the rest were illegal. This means that 15 in every 100 people in Thailand possess a gun.

Updated information, however, is not available from the SAS, but it is widely believed that actual gun possession is much higher.

The UNODC representative also noted that most of the illegal firearms in Thailand were obtained through trafficking in such weapons along the borders. This indicates that there are internal conflicts and ongoing instability within the country.

“For instance, on the borders with Malaysia, Cambodia and Myanmar we can see these flows of firearms going two ways, they can be more easily acquired. When you have instability, obviously you will have more availability of weapons.”

Uncommon but too familiar

Although deadly mass shootings are quite rare, gun violence is not uncommon in Thailand. Whether shootings occur between partners, family members, neighbours or even colleagues, people who follow the news are all too familiar with such stories.

Besides the Nong Bua Lam Phu massacre, one of the most recent shootings was in Ubon Ratchathani province in August this year, which involved two rival gangs in the parking lot of a superstore. Two people were killed and seven people were injured.

Another shooting occurred in Ayutthaya in the same month, where three people were injured in a gun fight in broad daylight, involving over a dozen men from two rival ice factories.

Apart from the accessibility of (illegal) firearms, the media also plays a huge role in influencing people to believe that having a gun is the only way to protect themselves.

Thai dramas often portray the use of guns as means to vent jealousy, anger, hatred or despair. Most scenes depict gun violence as a means to take revenge on enemies or to end tangled problems, such as love-triangles, fighting for inheritance or hierarchical oppression.

Feeling the necessity to possess a gun also indicates that Thai people have no trust in the state. As Thai criminologist, Associate Professor Police Lieutenant Colonel Dr. Krisanaphong Poothakool explains, people no longer believe that the police can effectively protect them when they are in trouble.

“On the other hand, why don’t people in the UK, Japan, or Singapore believe that they have to possess a gun? Because their government reassures them that, if there’s a crime, the police can take prompt action and provide justice.”

Gun welfare program

Thailand’s Interior Ministry also has a “gun welfare” program, where state agencies, such as the Royal Thai Police, the Customs Department and state enterprises, import guns through local gun traders for their staff at a much cheaper price.

Whether the reason is for self-defense, for protection of property, for sports or for game hunting, there is no limit on the number of guns an official can buy under this program. That means, they can use this “privilege” to purchase as many firearms as they wish.

“People nowadays have this belief that they should keep firearms as assets,” said Associate Professor Dr. Piyaporn Tunneekul, a criminologist from Nakhon Pathom Rajabhat University who does research on firearms possession in Thailand.

Under the gun welfare program, as Dr. Piyaporn explains, an official must retain possession of a gun for up to three years. Once the three-years expires, they can sell them. She feels, however, that the scheme should be limited to one firearm per person, and owners have to sell or destroy their old gun before purchasing a new one.

“That is why the statistics look very high, because one official possesses more than one firearm, while it is very difficult for ordinary people, like us, to acquire one. This reflects how guns are symbolic of power, and Thai people want to have power over others.”

Despite this “privilege”, what also remains problematic is how police officers, who have already been dismissed from service, still have access to these weapons. This is apparently the root cause of the Nong Bua Lam Phu mass murder, where the ex-policemen, who was fired from this job for drug abuse, used his guns to commit the crime.

Dr. Krisanaphong strongly believes that Thailand’s gun control should be increased and that the process for issuing gun licenses needs to be reviewed. Authorities should also consider revoking gun licenses of people who are convicted of serious wrongdoing.

“This is a loophole that we seriously need to look at,” he said. “So far, there has never been a review nor an investigation ofofficials or criminals who have been convicted of drug abuse or other serious offenses, or even those displaying aggressive behaviour, posting rude or threatening messages on social media. We don’t have such information on our databases yet.”

Solution

It seems like the mass murder at a childcare centre in Nong Bua Lam Phu province has, at least, prompted some changes.

Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha recently held his first meeting on gun and illegal narcotic control, to develop guidelines for solving drug abuse problems and gun-related violence effectively. They also discussed the idea of revoking the gun licenses of people who are deemed to be a threat to society or who are addicted to drugs.

The Royal Thai Police are also initiating the idea of confiscating weapons from police officers who misbehave or who are prone to gun violence, even if they are purchased legally. This measure may also include retired police officers.

Although amending the existing gun laws is the main priority, Dr. Krisanaphong thinks that both short-term and long-term strategies should also be implemented to curb gun-related violence.

“Once we learned that the gunman was an ex-policeman, who had a history of drug abuse and used his firearms to commit the crime, we now have to find out who else has been dismissed from the police force or been involved in drug abuse while on duty.”

Other strategies, as the criminologist suggests, include having clear rules on revoking gun licenses, as well as confiscating guns from police officers who have committed drug-related crimes or other serious offenses, to prevent similar tragedies.

Mental health evaluations of police officers who possess firearms, at least once a year, are also necessary as a long-term strategy.

The government should also set a limit on the importation offirearms under the “gun welfare” scheme, to avoid officers hoarding firearms.

“The amount of imported firearms must coincide with the number of officials who really need to use them, whether it’s police officers, soldiers or security officials,” said Dr.Krisanaphong.

“Let’s say you set a limit to no more than 5 million firearms across the country, authorities must find out whether the number of firearms in the market has reached 5 million. If it has reached the limit, then you cannot import any more of them,” said Dr. Piyaporn.

Similarly, the UNODC believes that gun measures need to be fixed at the regional, national and institutional levels.

“There are two main UN international instruments that exist. The first one is the UN protocol against illicit trafficking and manufacturing of firearms, and another one is the UN arms trade treaty,” said Julien.

“None of them have been ratified by Thailand or other countries in Southeast Asia.”

Apart from considering the UN’s international protocols on firearms, the UNODC suggests that the government seriously needs to revise the existing gun laws and contemplate the real purpose of gun possession.

Also, the police force and the military, which handle weapons on a daily basis, need to detect early warning signs as to whether certain officers are potentially dangerous and are likely to cause harm to others with the use of firearms.

In fact, one mass shooting is already way too many.

By Nad Bunnag and Jeerapa Boonyatus, Thai PBS World