THE TOP COURT’S RECENT VERDICT IN THE CASE OF KAREN FOREST DWELLERS HAS LEFT THEM WITHOUT THEIR TRADITIONAL LAND

SHORTLY after the helicopter took off, those left behind could hear the bamboo stalks breaking, making a sound like the crackling of wood burning in a fire.

The officials from Kaeng Krachan National Park offered a chopper ride to the elderly Karen, Ko-I Meemi, who honoured his daughter’s request that he move downhill from the steep-sloped upper mountain.

But the good wishes shared between the parties during the chopper ride would soon turn into hostile retaliation as each side staked out their legal and physical territory in what would become a high-profile case of alleged forest encroachment as well as alleged wrongful acts of the state against indigenous people.

Through thorough testimony,deliberation, and investigation by the Supreme Administrative Court and the previous court over the past six years, facts concerning the case have been pieced together and revealed to the public about what actually happened in the deep forest of Kaeng Krachan during the so-called Tenessarim Operation initiated by Chaiwat Limlikhit-aksorn, the new park chief at that time.

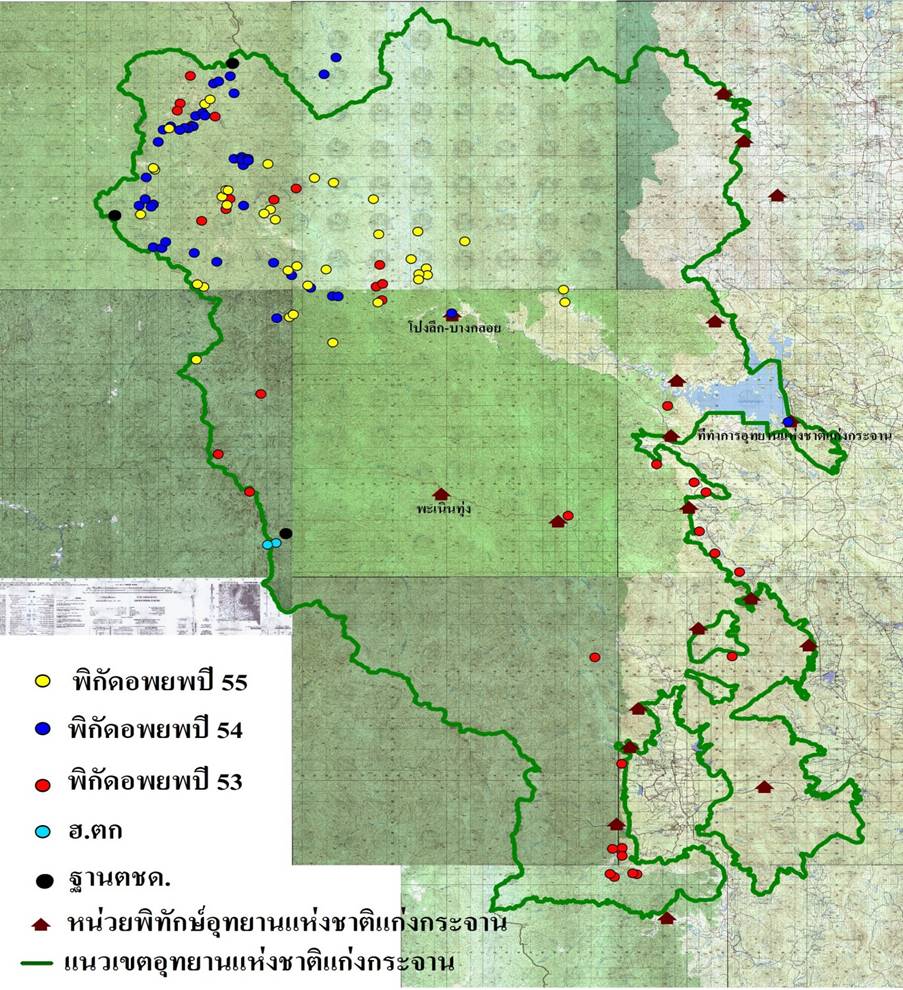

As he took up the position at the park in Phetchaburi province in late 2009, as noted in the park’s summary report and the courts’ verdicts, Chaiwat initiated the operation in 2010 in an attempt to push back so-called “encroachers”, claimed to be “a minority group” from the Thai-Myanmar border.

The park and some concerned senior park officials had acknowledged that these people tended to cross the border and travel through the Phachee River Wildlife Sanctuary adjacent to Kaeng Krachan. There, in the deep mountains they would occupy plots of land vacated by Karen occupants, especially the two communities of Bangkloi Bon (the Upper Bangkloi), and Jai Pan Din (the heart of the land).

The Karen of the two communities, 56 families including Ko-I’s, had been relocated from those communities during the park’s relocation plan in 1996 to new villages – Bangkloi Lang (the Lower Bangkloi), and Pong Luek – below and have resettled there since.

The park officials claimed that they had confirmation from community leaders that none of the residents of the two upper villages in the deep mountain had moved back there following their resettlement below.

After some negotiations with the so-called encroachers during their first three operations, the team of park officials and military officers, in their fourth operation in mid-May 2011, decided to burn the dwellings and contents found on the plots of land_98 in total.

Their reasoning, they later told the court, was that they could not leave the properties to be reoccupied again after they had found several instances of wrongdoing in the area, including forest clearing, harvesting of large trees, and marijuana-growing.

After a series of property burnings, six Karen, including Ko-I, emerged, claiming their homes in Bangkloi Bon and Jai Pan Din had been burned down along with their belongings as a result of the operation. They later filed a complaint with the Administrative Court on May 4, 2012, accusing the park officials of having used excessive authority without advance notice.

They argued that the operation had thus been unlawful, and had violated the Constitution that guaranteed community rights. As well, the action broke several international human rights conventions, including the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD), along with the Cabinet Resolution issued in 2010 to secure Karen’s rights.

The Karen called for restitution worth Bt9.53 million to come from Chaiwat’s supervisors, the Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation, and the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment. They also called on the court to allow them to relocate to their old villages of Bangkloi Bon and Jai Pan Din and to require that the two defendants follow the 2010 Cabinet resolution.

“The burnings on properties of the six plaintiffs are unlawful as it was an administrative act out of proportion,” claimed the six plaintiffs’ complaint to the court. “This resulted in the six losing their homes, food and clothes and was thus a violation against them.”

The truth told

Following deliberations at the first court trial, the court declared as facts that the six plaintiffs were Karen who lived in the Bangkloi Lang and Pong Luek villages below, and the controversial plots in the deep mountain were newly cleared forest land with no indication they were traditional and old communities. As such the six plaintiffs had violated the National Parks Act, the court pointed.

Furthermore, it said the park officials had conducted three operations before burning down the properties and had negotiated terms with the encroachers they had met. In the other three operations, the team had used helicopters to get to the villages, the court noted, while Chaiwat and other community leaders travelled by foot to get there. Along the way, they learned about wrongdoings, including clearing forestland, harvesting large trees, and growing marijuana.

Despite the terms that had been previously negotiated, those discoveries legitimised their subsequent burning activities as proportional and lawful and they had followed the authority given to them under Section 22 of the National Parks Act, the court stated. Their actions thus did not violate the six plaintiffs as complained, said the court.

In view of the court’s ruling that the controversial plots of land were newly cleared, the six plaintiffs had no rights to claim and were not entitled to protection of rights against administrative orders issued by Chaiwat, the court said. And Chaiwat had no need to come up with advance notice procedures.

Finally, because the officials’ authority was considered lawful, they had thus not violated the Constitution and other conventions.

However, the court said that because it was in the park officials’ capacity to take their belongings out of the properties before burning down, it was a violation caused by the enforcement of law.

“The National Parks Department must compensate the loss of their belongings at Bt10,000 per person,” the court ruled.

Both parties in the conflict, however, decided to appeal to the Supreme Court, which heard the case and issued its verdict on June 12.

After considering all testimony, investigation, and deliberations, the Supreme Court pronounced the facts and concluded that the six plaintiffs were indigenous Karen who did, indeed, live in Bangkloi Bon and Jai Pan Din villages deep in the mountain of Kaeng Krachan.

But there was a complication: the Karen land was located in a Forest Reserve declared in 1965 and in 1981 was incorporated into Kaeng Krachan National Park. In 1996, these people had been relocated to Bangkloi Lang and Pong Luek, but felt they could not continue there because it was not in harmony with their way of life. Some returned to their old communities and continued utilising the land, the Supreme Court declared.

The court decided that the Karen had the right to file the original complaint on May 4, 2012 and had done so on time, within one year after the incident took place.

There was another issue to consider, the court pointed out: Did the officials violate the rights of the Karen and, if so, what compensation should they get? To analyse this, the court said it needed to consider first whether the officials had burned the six plaintiffs’ properties.

Based on all facts checked, the court found that the defendants’ testimonies and Chaiwat’s testimony to the National Human Rights Commission had demonstrated that there was an order issued by Chaiwat to demolish and burn the properties, thought to be of the “encroachers” the officials had negotiated with. As well, a “wrongdoer” was arrested, later identified as Ko-I’s son, prompting the court to conclude that the incidents, had in fact happened to the six.

The court then turned to whether or not the action had violated the six.

According to the verdict, the top court declared the Karen to be indigenous people who lived in Bangkloi Bon and Jai Pan Din. But because the land had been declared as being located in a park, and they had no land documents to show their rights, the Karen had thus violated Section 16 of the National Parks Act, which prohibited people from occupying forestland.

The officials, on the other hand, have authority under Section 22 to remove properties that encroached on forestland, but it must be done within the law, especially if it were likely to affect people’s rights.

Section 22 is actually accompanied by procedures that require that the accused be informed officially and in writing, before action is taken against them.

The court stated that although the officials had enforced the section and met the intention of the law, the law still did not allow them to use their judgement and discretion.

The action, the court pointed out, had seriously and excessively affected the plaintiffs’ rights. Thus, the officials’ action amounted to an excessive exercise of power and failed to follow proper procedures. Furthermore, it violated the 2012 Cabinet resolution requiring officials to cease actions against Karen and instead provide them protection in controversial situations.

Therefore, the court declared, the officials’ action was unlawful, caused damage and must be subject to liability.

The court then ruled that the defendant officials must be held responsible to compensate for the burned properties of the six Karen, in addition to their belongings, worth in total Bt50,000 per Karen, within 30 days of the verdict being issued.

The lost land rights

Things would be different if the land laws had been written otherwise.

According to land rights experts, land was distributed to people after a major reform during the reign of King Rama V, when the first land deeds were issued to ordinary people, as well as laws promulgated concerning land rights.

The critical point of change was made following the sixth land deed issuance law in 1936, when land occupation and utilisation by ordinary people nationwide was recognised – including that of indigenous people.

Then 18 years later, in 1954, the Land Code was formalised, and a land document issuance system introduced as a result. People occupyingland before the Land Code was in efffect were required to inform the state and to get Sor Kor 1 documents in order to be able to secure the land-deed, which is a critical condition for affirming a person’s land rights.

Those having land rights recognised before the 1936 sixth land deed issuance law were still allowed to claim land deeds. However, they were also required to declare their right to occupy lands and have the Sor Kor 1 document, following the coup order in 1972.

But more critical is that the law nullified their previously recognised land rights if the land was declared as part of a reserved or protected forest area. This was addressed again in 1985, when the Land Code was amended, with land surveys conducted and forestland removed from the issuance of land documents.

Retired General Surin Pikultong, a former member of the state land encroachment resolution committee and now a chairman of an executive committee resolving spiritual and habitation issues concerning Karen land, said that during those years changes in land rights took place, and the Karen were deprived of their land rights. The Karen were reclassifed as “encroachers” on their own land, despite their land rights having previously been birthed and recognised.

Surin said the state had repeatedly attempted to address the issue, putting forward several amendments to laws and Cabinet resolutions, but they all floundered over the failure to first recognise their land rights, he said.

Concerned officials, he added, need to carefully study the issue and ensure they have full knowledge before taking action.

As the rights of the Karen to land was previously recognised by the state, Surin says they should be seen as still existing. Officials should screen out encroachers to differentiate them. They should also seriously work on demarcation to determine territories. Establishing clear boundaries, he said, should help officials control encroachment and impacts on forest ecosystems as well.

“It’s not just about law, but the rule of law,” said Surin. “The problem that we have is we don’t know about it, or do not know enough.”

A longtime land rights expert, Asst Professsor Eathipol Srisawaluck, of the Thailand Research Fund’s Land Forum, said it would be impossible now to claim land rights recognised by the state as the laws were in place and they were applied to everyone.

In recent years, Eathipol said, the government has been attempting to resolve the issue through Cabinet resolutions to assign land use rights to those having conflicting claims in forest areas. He agreed that it’s a policy that needs to be addressed, and the officials just have done their best by following the laws.

New mechanisms to take care of social components need to be developed and introduced to help settle the issue, Eathipol said, adding that the national land policy committee has just resolved to introduce such measures to deal with it.

As for Chaiwat, he said after the court ruling that he accepted the Supreme Court ruling, and was glad that at least people were not allowed to return to live in the forest he fought for. Surapong Kongchantuk, a human rights lawyer who helped the Karen in the case, meanwhile, still places hopes on the 2010 Cabinet resolution to make way for the Karen to return to their old villages in the deep mountain.