When a British charity worker got engaged to a young Ukrainian woman, he thought he was building a new life for them both in Odessa – he was wrong.

James’s car pulled up at the Villa Otrada. The 52-year-old British charity worker had been looking forward to this moment for months.

He was excited to see his fiancee, Irina, waiting for him outside the restaurant on Ukraine’s Black Sea coast. Twenty years younger than him, she looked glamorous, her blonde hair fresh from the hairdresser.

Not far away were what James thought were Irina’s parents and 60 invited guests, also dressed to the nines.

James got out of the car and the waiting crowd turned to clap.

It was July 2017, the start of a hot summer in Odessa, and tables had been laid out on Villa Otrada’s terrace overlooking the sea.

Moments later, James and Irina recited their wedding vows under an arch of flowers.

But what should have been the perfect moment was in fact nothing of the sort. By midnight James was lying alone in hospital, sick from a suspected spiked drink. He was married, but it wasn’t to the woman he loved. It was the couple’s wedding planner.

This is a story about how a British man lost most of his life savings, as well as his dignity. And how Ukraine’s justice system laughed in his face.

James is not his real name.

Such is his embarrassment that he’s told no-one in the UK his story, not even his family. The BBC has verified his account of what happened using bank documents, official records, text messages, and interviews with many of those directly involved.

Sherlock Holmes?

A sign showing the silhouette of a man in a hat with a pipe sticks out above the pavement of Lanzheronivska Street in central Odessa.

Follow the yellow-and-black arrow through the archway and across a courtyard, and you reach the office of Robert Papinyan, private investigator.

The former policeman is well-dressed, with dyed black hair. Everything is on brand. There’s a Sherlock Holmes notepad, Sherlock Holmes business cards and his ringtone is the theme tune of the Soviet TV version of Sherlock Holmes (which many in the former Soviet world argue is the best).

As it turns out, Mr Papinyan’s methods bear little relation to that of his fictional hero on Baker Street.

“We don’t work with the police, we use psychological methods,” he says with a chuckle. “This money was taken illegally, so we have to use kind of illegal ways of getting it back.”

A block away from Mr Papinyan’s office in Odessa is Deribasovskaya Street. It’s the entertainment heart of the city, full of restaurants and bars.

Walk down it in the evening and you’ll almost certainly see Western men dining out with much younger Ukrainian women, a bag of expensive designer gifts sitting on the chair beside them.

Ukraine is one of Europe’s poorest countries, with an average wage of about $350 (£247) a month. There’s a thriving “dating” industry here. It’s multi-faceted and ranges from pay-per-mail email services to face-to-face “romance tours”, where Western men pay thousands of dollars to meet a series of prospective young Ukrainian “wives”.

But James says he didn’t come to Odessa looking for love.

A charity worker living in the UK, he was asked by a friend in 2015 to help set up a new project supporting children fleeing the conflict zone in Ukraine’s east. Europe’s second-largest country had just undergone a revolution, and Russia had responded by supporting a rebel uprising.

Working abroad was new to James, but he threw himself into it with the help of a translator called Julia. For several months he shuttled back and forth, combining his voluntary work in Odessa with his full-time job in the UK.

Then that winter, a heavy snowfall brought their work in Odessa to a halt. There wasn’t much to do, so Julia suggested that James might like to go on a date with one of her friends.

That friend was Irina. Then 32 years old, she was from Donetsk, one of the cities in eastern Ukraine that are now occupied by Russian-backed fighters. It soon became clear that her troubled past went much deeper than just fleeing war.

“She immediately told me about two previous marriages and why she didn’t want to marry a Ukrainian man again,” James says.

There was an age difference of 20 years but James says they got on “like a house on fire”. The couple went out for a few evenings in a row, enjoying Odessa’s nightlife.

James had fun with Irina, but they were never alone. Irina spoke minimal English and James no Russian or Ukrainian. So as is the case with much of Odessa’s “dating” scene, a translator, in this case Julia, was always there – and getting paid up to $150 (£107) a day.

“It was a bit weird having someone repeating whatever was being said. But there was a chemistry between us,” says James.

Perversely when they were apart, communication was easier. They flirted through the messaging app Viber, which has a translation function.

“You gave me a real fairy tale. And thanks so much for that… I believe in YOU. Just you can give me this happiness. I love you,” one message she sent James says.

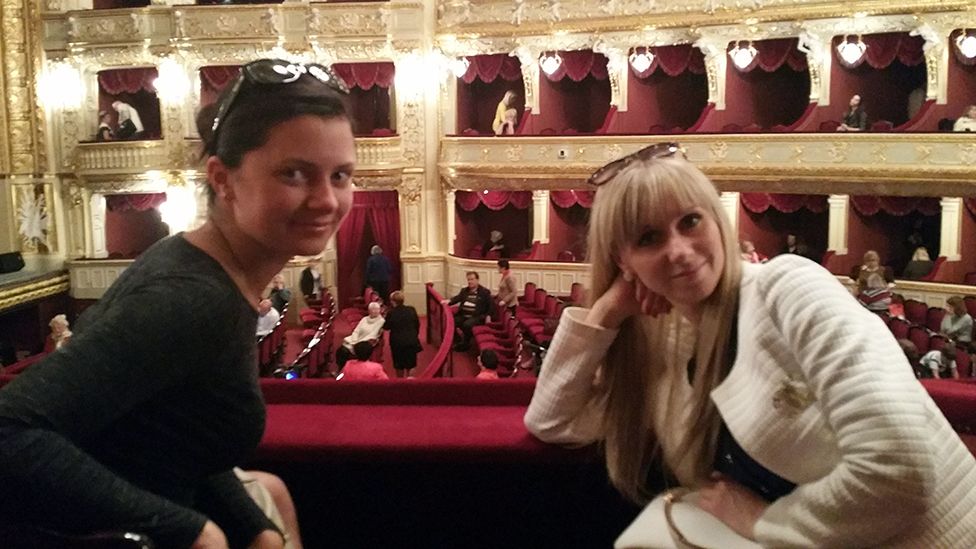

Over the next six months, the new couple saw each other whenever James came to Odessa. There were expensive meals and evenings at the Opera House.

But intimacy, even kissing, was off-limits. Translator Julia was always there and Irina told him she didn’t believe in sex before marriage.

“I thought: ‘That’s a very high moral standard’,” James says. “She’d obviously been brought up very well.”

Engaged to Irina

Eight months before the wedding reception, the pair held an engagement party at the same venue, Villa Otrada. A video shows James and Irina dancing slowly on the dancefloor. He’s moving stiffly, she’s smiling and waves at the camera.

Glitter is falling from the sky as Whitney Houston’s ballad Could I Have This Kiss Forever echoes across the function room. It’s November 2016, 11 months after their first date.

James had popped the question after some firm prodding from both Julia and Irina. He says he’d fallen in love but had no illusions about the strength of Irina’s feelings.

“She felt so trapped in her country,” he says.

“She was obviously intelligent and wanted to create another future outside Ukraine. The connection was a sort of shared interest.”

James began paying for Irina to have English lessons. The hope was that it would pave the way for her to move with him to the UK. But after a few chats with embassy officials, it was clear that the bureaucratic obstacles to a move were huge.

“It was going to take several years,” says James.

So he took the plunge, deciding to move to Ukraine and start a new life with Irina. He quit his job and sold his house, and with Irina’s encouragement they began looking for a place to live together in Odessa.

“Buying was expected,” he says, “because it gave a sort of permanence to the relationship. My friends in the UK thought it was a big step but they were happy for me that I had a future.”

In fact, James’s problems were just starting.

The apartment

Transferring money from the UK to the Ukraine is never straightforward. Ukraine is one of Europe’s most corrupt countries and has had several high-profile banking scandals. Money-laundering controls mean there are limits on the size of the transfer, and big numbers quickly attract attention.

So it wasn’t a complete surprise to James when Irina suggested an unusual arrangement to get his $200,000 (£141,000) of “apartment” money to Ukraine.

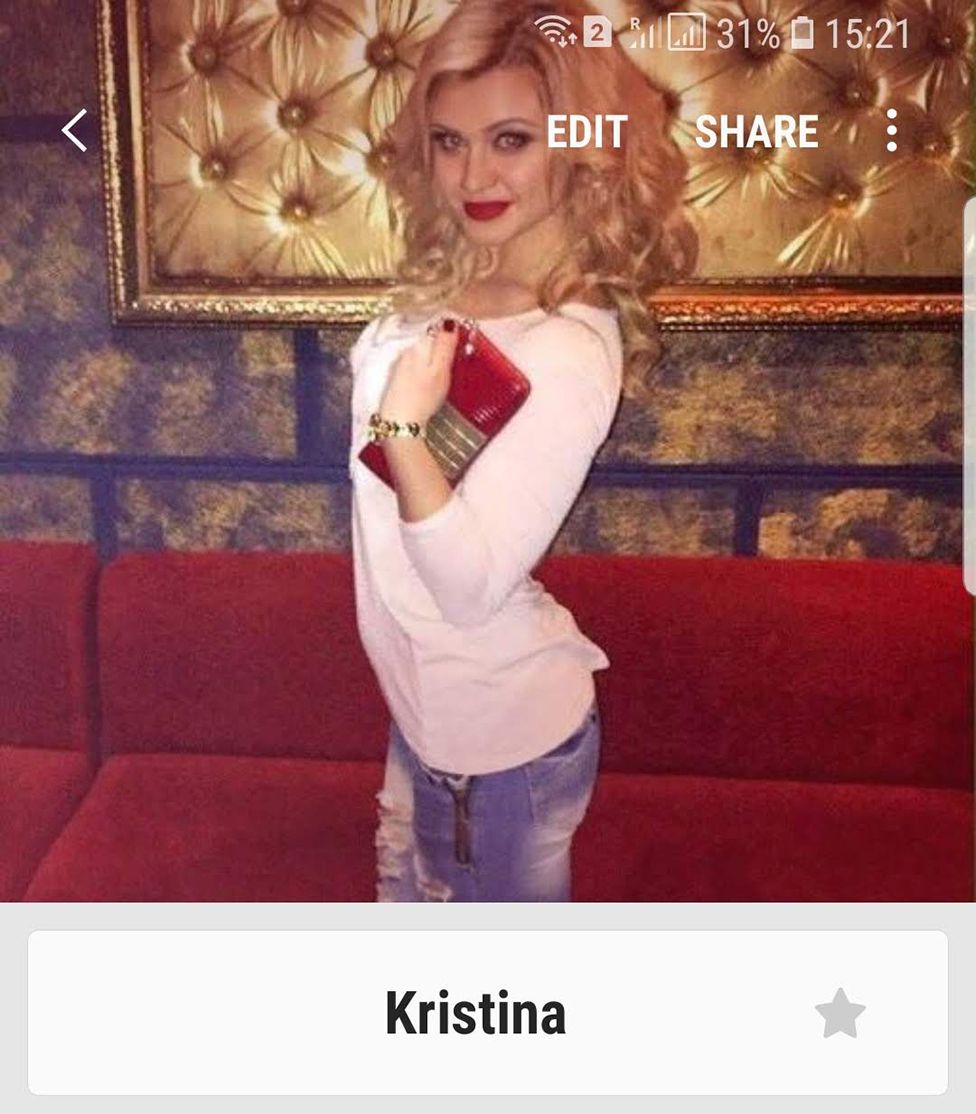

Instead of putting the money in Irina’s personal account, James was told he should put the money in the company account of her friend Kristina, the wedding planner.

Despite some misgivings, James wired the money to Kristina. When the money arrived in Ukraine things took a surreal turn.

Irina announced to James that the bank would only release the money if he was legally married to Kristina. It would be a formality, completed in just 10 minutes in a registry office and unpicked at a later date, she said.

James was now in an impossible situation. With just days to go Irina was threatening to call off their wedding unless the money was released and they had a home to move into.

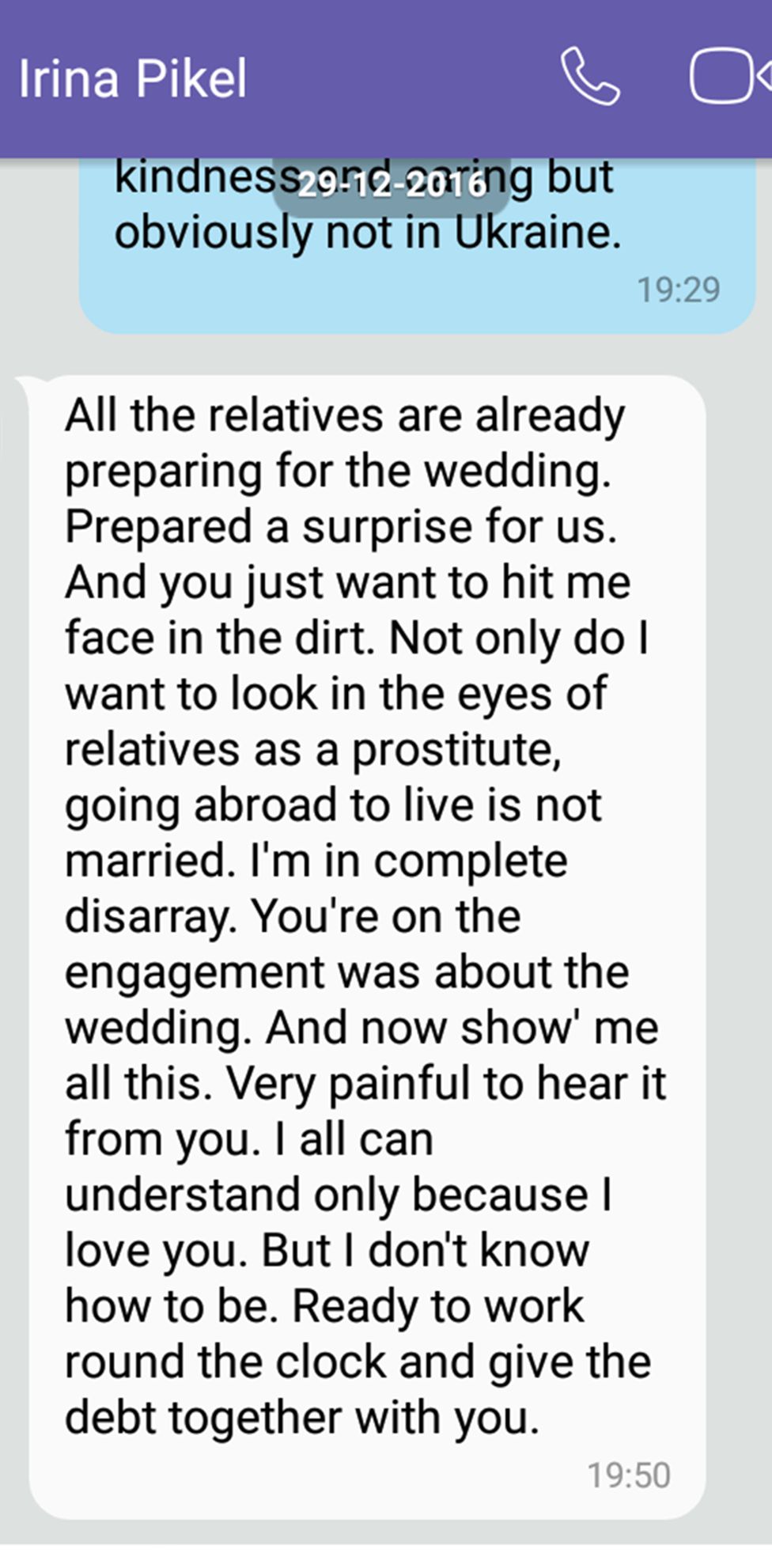

“I’m in complete disarray,” Irina told him in a Viber message. “You want me to look like a prostitute in the eyes of my relatives.”

“I was being threatened with the thought of 60 guests at the wedding including her family,” James says. “They’d all be coming round beating the crap out of me if I didn’t go ahead with the marriage because I was letting Irina down.

“I was told that divorcing Kristina then re-marrying Irina would be an easy thing to do.”

So on Friday 10 July 2017, with the encouragement of his fiancee Irina, James married the wedding planner Kristina Stakhova.

Irina was “jumping up and down,” James said, “she was happy now”.

With good reason. The money was released and that very afternoon Kristina and Irina announced that all of the $200,000 had been spent on an apartment. He would later discover the new place had actually cost just $60,000 (£42,310) and was not his alone, but jointly owned with his legal spouse (the wedding planner) Kristina.

“I was such an idiot,” James would later say.

The wedding reception

The day after marrying Kristina, James’s taxi pulled up at his wedding reception to Irina at the Villa Otrada. His plan was to do everything apart from the legalities – go ahead with the wedding before sorting out a quickie divorce to Kristina and a new legal marriage to Irina.

As always James paid for everything.

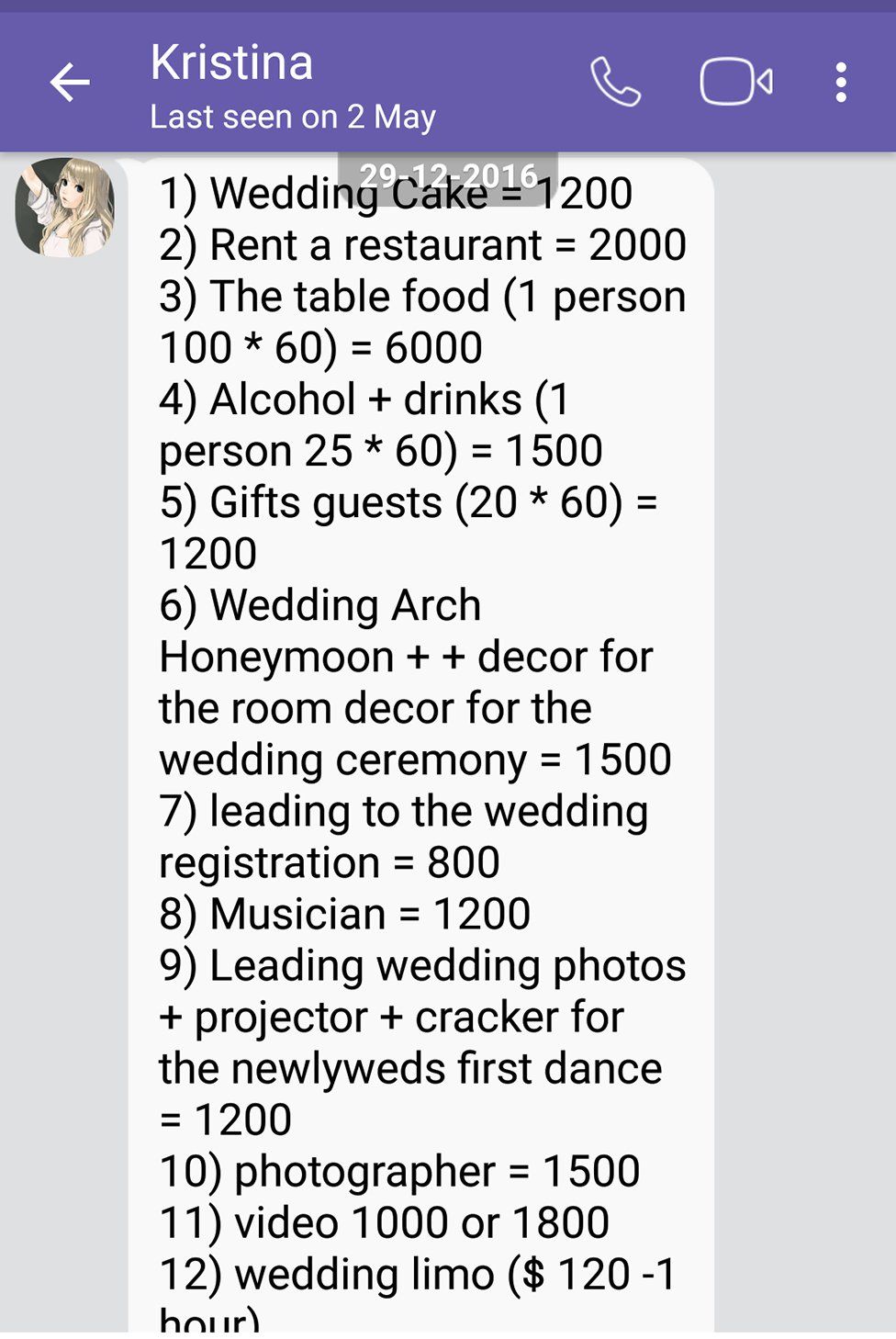

Ukraine is a cheap country by European standards, but you wouldn’t have guessed it from Kristina’s $20,000 (£14,100) itemised wedding bill.

With the benefit of hindsight, James now knows that everything about the wedding reception was a scam.

The prices were inflated, the 60 guests most probably paid to be there, even Irina’s “mother” turned out to be Julia the translator’s mum. He was almost certainly the only one attending who thought it was real.

James didn’t know it at that point, but his fiancee Irina already had a husband. Official records seen by the BBC show that she’s been married to Andriy Sykov since August 2015, three months before she met James.

Kristina the wedding planner also had a husband, called Denys, but he was apparently more willing to play along. Records show Kristina divorced Denys three weeks before she signed the paper to marry James. Once the scam marriage was over, she married Denys again.

The evening of the wedding reception, with a first-ever night of intimacy between James and Irina looming, drastic measures were taken. James believes he was drugged by the person who he thought was Irina’s mother.

“She was plying me with drinks and I’m now sure it was spiked, I started violently shaking and had to be taken out.”

James ended the night in hospital. Irina refused to go with him and the next day accused him of getting drunk and humiliating her in front of her family.

For the next few weeks Irina kept her distance, saying she herself had medical problems but that James couldn’t visit her in hospital.

“I’m in hospital and you cannot come because you are not my husband.” Irina messaged James on Viber. “In passport your wife is Kristina. So with me can be only my mom.”

James still transferred her more than $12,000 (£8,460) for her “medical costs”.

Eventually the madness stopped. A friendly Ukrainian intervened, and broke it to James that the real value of his apartment was just $63,000 (£44,632) – $140,000 (£98,730) less than he’d paid.

James finally realised that the women had scammed him out of about $250,000, two-thirds of his life savings.

“My heart fell into my boots.” he says. “It goes beyond the level of human understanding that all these people would behave like that and think nothing of it.”

Tatyana is an official translator who tried to help James pick up the pieces after the scam.

“Every year we hear stories of people being ripped off in Odessa but this scale of disaster is different,” she says.

No justice

Somehow James avoided sinking into deep depression. Instead he focused his energy on getting his money back – and getting justice.

“I had all the bank documents for the transfers, and the Viber messages between us,” he says. “I was sure it would be sorted out.”

But he was about to get a crash course in the inadequacies of the Ukrainian justice system.

Four times he went to the Odessa police, giving his account of what had happened and the evidence he’d collected.

“At times they laughed in my face,” he said.

Ukraine’s police force, and Odessa’s in particular, have a pretty rotten reputation for fighting crime. Marriage scams, even unusual ones like this, are a long way down their list of priorities.

“There are cases here when the police here don’t do anything and don’t move,” Anna Kozerga, James’s lawyer says. “We have to keep asking them to take action.”

Getting the police to act often involves bribing them but it was something which James refused to do.

Irina and Kristina were taken in for questioning but despite James’s documents and Ms Kozerga’s prompting, no charges have been brought against them.

We contacted the police in Odessa but they declined to comment on James’s case.

The only progress has been that after James’s marriage to Kristina was ruled bogus, he was named the sole owner of the $63,000 apartment. He’s holding on to it in the rather forlorn hope that its value will rise once the Covid pandemic is over. But there’s no way it will get close to the $200,000 he paid for it.

Playing the game

With the police uninterested, James has thrown in his lot with Robert Papinyan, Odessa’s unorthodox Sherlock Holmes.

“We’ve tried the police and everything through the correct channels,” James says.

“You have to play the game unfortunately.”

The “game” means paying the investigator $3,000 (£2,115) up front, and 30% of any money recovered.

There’s no secret about Mr Papinyan’s methods. He freely admits to us that “intimidation” is one of his tools.

When we visit his office, three heavy-set men are sitting in the entrance. Mr Papinyan believes that the women were the driving force behind the scam but has been communicating with them through their husbands.

Mr Papinyan shares their contacts and we reach out. Kristina’s two-time husband Denys sends us photos of a car that he says has been following him and complains that Mr Papinyan’s men are “extortionists”.

Irina’s husband Andriy replies that there must be a mix-up and that he would pass our contacts to his wife. She never gets back to us but we find her dating profile still up online. She’s listed as a divorced babysitter and promises, “My heart will belong to one man and only one.”

From the UK, James now swaps translated Viber messages with Mr Papinyan rather than Irina. He’s still hoping that he might be getting some more of his money back.

“My guys were in the city of Chernomorsk (near Odessa), two weeks ago,” goes the latest Viber from the private investigator.

“We found Irina near the house. We gave her until June 20 to resolve the issue of debt repayment.”

James has endured too much to get his hopes up. He’s got another charity job now and is trying to move on. Part of the reason he’s concealing his identity is that he doesn’t want his employers to be alarmed. Being scammed out of a quarter of a million dollars doesn’t look good on the CV.

“I haven’t told my family what happened either, it would just upset them.”

And what would you say to someone who reads your story and says “What a fool!”?

“They’d be right,” he says.

James says he decided to tell the BBC his story to warn others tempted to seek romance in Ukraine.

One crumb of comfort he takes away from it is that Britain’s foreign office has modified its Ukraine travel advice to reflect his painful and costly experience.

“There have been incidents of marriage fraud and attempted extortion affecting foreign nationals,” the website now reads, before concluding: “Unfortunately it’s very unlikely you’ll be able to recover your money if you’re a victim of such a scam.”

What is romance fraud?

According to Action Fraud, romance scams involve people being duped into sending money to criminals who go to great lengths to gain their trust and convince them that they are in a genuine relationship. Their requests might be highly emotive, such as criminals claiming they need money for emergency medical care, or to pay for transport costs to visit the victim if they are overseas. Scammers will often build a relationship with their victims over time.

- Be suspicious of any requests for money, particularly if you have only recently met online

- Speak to your family or friends to get advice

- Profile photos may not be genuine – use a reverse image search to check photos have not been taken from somewhere else

If you think you have been a victim of a romance scam, do not feel ashamed or embarrassed – you are not alone. Contact your bank immediately and report it to Action Fraud.

bbc