One evening in 1993, Mits Sahni was standing in a queue in Leicester Square in central London.

He was trying to get into a nightclub – but when he got to the front of the line he was turned away by the bouncer.

It wasn’t the first time this had happened.

He’d tried different approaches – bringing along female friends or wearing smarter clothes. But the result was always the same. “The doorman would make up excuse after excuse.

And after a while you figured out it was due to racism.”

Mits had always been into music.

As a 10-year-old in Ealing, west London, he’d take his boombox and a sheet of lino into school and breakdance to hip-hop in the playground at lunchtime.

On Saturday afternoons he’d take tapes he’d edited on his mother’s double-cassette hi-fi system to Ealing shopping centre and play them full volume on the stereos in Dixons.

Then he’d go to a fast food joint and breakdance for customers in return for a bag of chips.

His first experience of clubbing came in 1987. It was a Friday and, now 14, he had bunked off school to go to a daytimer – a music event for British South Asians held in the middle of the day.

About 10 of his friends had left the house that morning in school uniform so as not to raise their parents’ suspicion.

They met outside a nearby supermarket and went as a group to the Empire Ballroom.

It left a deep impression.

There were live bands playing bhangra – traditional Punjabi folk music reworked with new electronic production techniques – and DJs who mixed bhangra with reggae, soul and hip hop, creating a new sound. “You just saw them rocking out a place of 2,000 people,” Mits says.

Another revelation was that divisions in the British South Asian community disappeared. Seeing the younger generation, whatever their backgrounds, moved by the music on the dance floor, he realised: “So this is how you bring people together.”

But Mits’ real love was hip-hop. He bought his first set of turntables with money he saved up from a part-time job at his uncle’s luggage shop, and formed a group called Hustlers HC with two friends, Paul and Mandeep, from the gurdwara – the Sikh place of worship he attended on Sundays.

Punjabi Sikh men in turbans rapping with politically conscious lyrics on subjects such as racism raised eyebrows on the Asian music scene, where audiences generally expected bhangra, but these songs helped give Mits and his friends “a sense of identity”, he says.

By the time Mits was standing in the queue in 1993 trying to get into that big London nightclub, he was 20 and had already had some success as a DJ.

He was putting on his own events at colleges, which were proving popular. He was also DJ-ing at different locations across the capital.

But there still wasn’t a regular club night at a well-established venue specifically for a British Asian audience.

“They didn’t think that British Asians drank, so they were worried about lack of revenue from alcohol,” says DJ Ritu, another popular British South Asian DJ.

“They just didn’t think that the events would be successful.” And she thinks there was possibly an undertone of racism too.

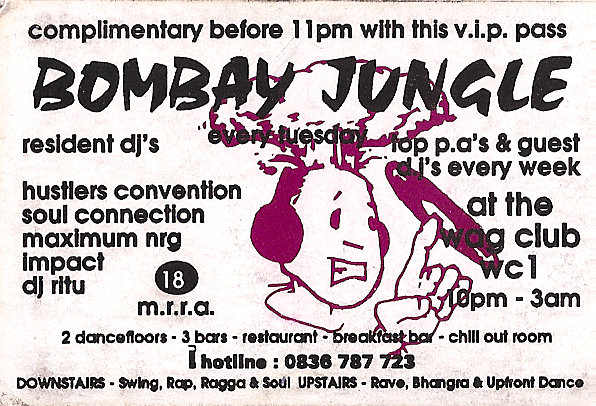

But then suddenly the Wag Club in Soho, having seen the popularity of daytimers and student union nights for British South Asians, made it known that it was interested in running a weekly British Asian night on Tuesdays.

This was a world-renowned club, which attracted stars like Grandmaster Flash, Afrika Bambaataa and Sade, and welcomed guests such as George Michael, David Bowie and Neneh Cherry through its doors.

The Tuesday Asian night was an exciting opportunity, so Mits and his friends, Mark Strippel and Matt Thomas, offered to run it.

And their offer was accepted.

From being one of those left on the street outside in nearby Leicester Square, Mits was about to become an insider at one of London’s coolest nightclubs – albeit on a Tuesday, known as the “graveyard night”.

The first event would be in September and would be called Bombay Jungle. DJ Ritu would be one of the resident DJs.

Mits, Matt and Mark went around universities handing out fliers. They weren’t sure whether anyone would turn up.

But on the first night, there were around 300 people. “We were like: ‘What?!'” says Mits. “‘People actually coming to see us?'”

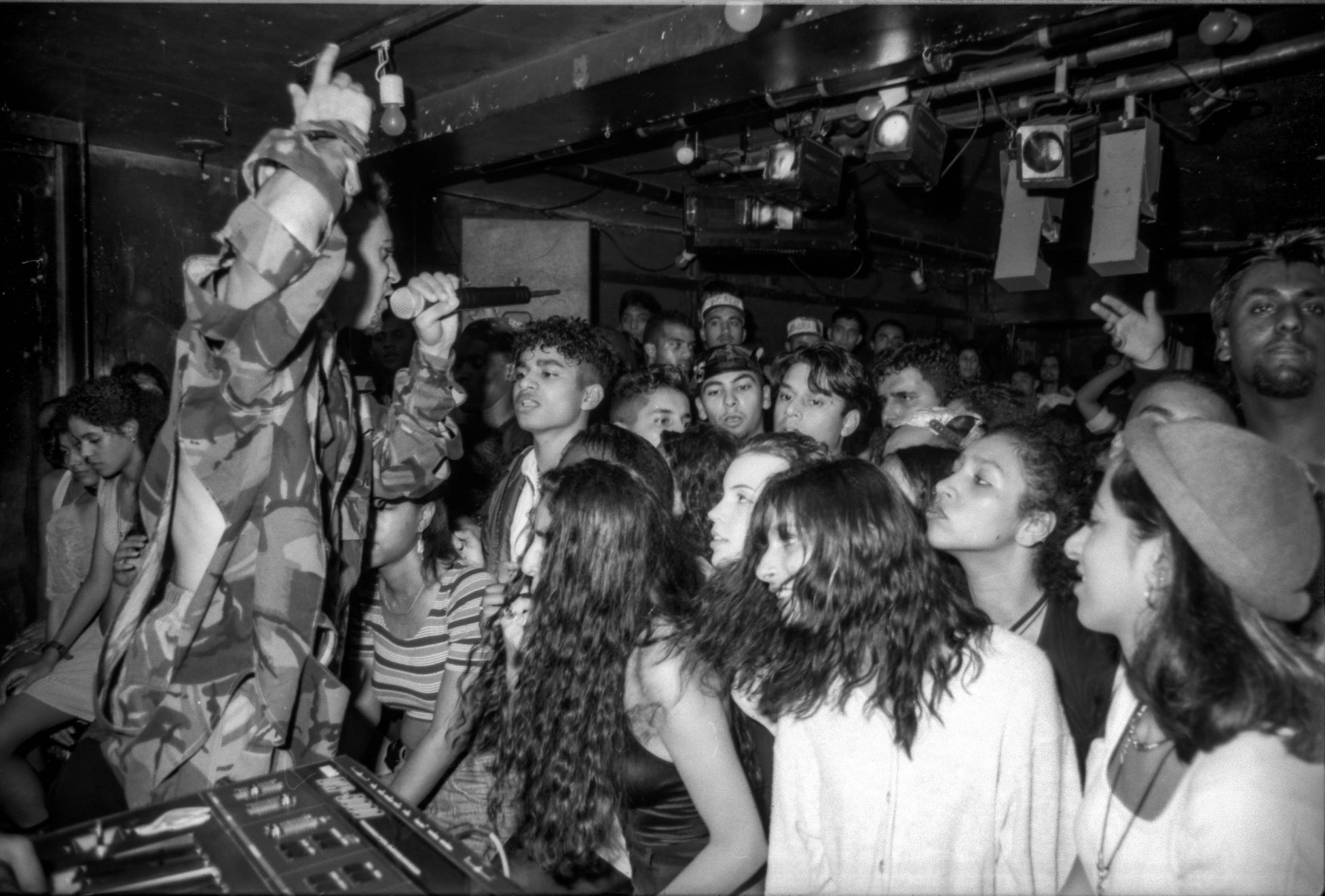

In a few weeks, word had got round. Mits says up to 800 people were queuing outside, hours before the event started at 21:30.

Coaches were soon coming from Leicester, Birmingham and Manchester. “It just went from there,” Mits says. And no-one was turned away unless the club was full up.

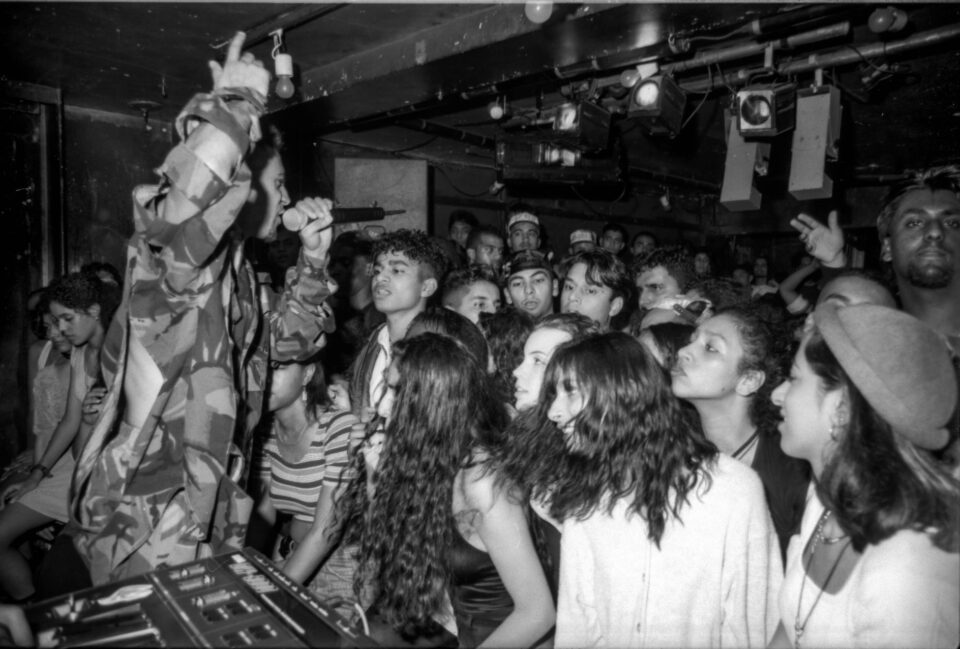

The clubbers were all dressed in the fashion of the time.

The men wore baggy jeans, puffer jackets, shell suits; the women wore black dresses or spangly tops and jeans.

There were two floors, one played hip hop, reggae and ragga. Upstairs was bhangra. “Ironically, Mark looked after the bhangra floor,” says Mits. “And there was me and Matt in the downstairs basement, which was the hip hop floor.

So it’s like the Sikh guy was looking after the hip hop and the white guy was looking after the bhangra.”

For British South Asians, Bombay Jungle was an important development.

“What Bombay Jungle did, it allowed all these music genres to come together on the dance floor in the same space of the club.

It was a new way to listen and dance to a varied ensemble of music and express oneself on the dance floor in a mainstream space,” says Rajinder Dudrah, professor of cultural studies and creative industries at Birmingham City University.

Most of the British South Asians who came along, Mits says, were university students. “Suddenly they were free.

They had moved out of home, no Mum and Dad to argue with about where you’re going – you can get totally drunk, party as much as you like.

And that was it. And it was just them experiencing their freedom.”

Any fears that the bar takings would be disappointing were put to rest. “They drank like fishes,” Mits laughs.

There were other cultures that were more dominant in terms of fashion, in terms of music, in terms of acceptance and coolness DJ Ritu

Bombay Jungle didn’t only attract young British South Asians.

Mits recalls that some weeks into the launch he was upstairs on the bhangra floor when he saw three Jamaican women. He went up to them and asked if they liked the music. “We absolutely love it!” they replied.

DJ Ritu says the dance floors at the Wag Club on Bombay Jungle nights were heaving.

She smiles as she remembers people with their hands and arms in the air. “It was very celebratory, very euphoric and tribal.

It actually becomes a complete adrenaline rush for a DJ, or it was for me, when you see that kind of energy and euphoria on a dance floor in front of you.”

Bombay Jungle lasted for two years at the Wag Club and helped pave the way for British Asian music nights across the country, extending beyond the university scene.

Dr Dudrah says it allowed music creatives “to spin their vinyls, play their digital beats and mix and match a range of music in their own unique ways… it helped them develop their careers in the music industry”.

DJ Ritu went on from the Bombay Jungle nights to be one of the founders of Outcaste Records and Club Outcaste, as well as Club Kali for the LGBT community.

Talvin Singh, who would go on to win the Mercury Prize in 1997, founded the Anokha club night with Sweety Kapoor in east London, which saw an older, more cosmopolitan crowd.

He and other musicians like Punjabi MC and Nitin Sawhney then helped take British South Asian Music into the mainstream.Looking back, it was ground-breaking… to break down those boundaries that were put up for us and just to see Asians get into clubsMits Sahni

DJ Ritu, who continues to work as a DJ and radio presenter, says the ’90s were an important moment for second generation British South Asians.

At the start of the decade, she says, there was a sense that it wasn’t cool to be Indian, Pakistani or Bangladeshi.

“We were a set of mixed communities, we weren’t a homogenised community, and largely we were marginalised, we were stereotyped, we were easy targets, easy prey for racists.

So how many people really wanted to be outwardly and obviously Asian, or wear their Asian-ness on their sleeve with pride?” she asks. “I’m not saying there weren’t people that did have a lot of pride in their culture.

Of course there were. But there were other cultures that were more dominant in terms of fashion, in terms of music, in terms of acceptance and coolness.”

But by the end of the decade, she thinks that had changed.

“If I look back on my life, the ’90s stand out for me as just being absolutely revolutionary,” says Ritu. “And just like thinking, yeah, you know, we’ve done it.

We’ve done it. We’re not just a trend that gets picked up for a week or two or even a year. Culturally, we were on the map.”

Mits agrees. He’s still in the music industry working as a live music promoter.

“Looking back, it was ground-breaking. It was the passion that drove us to break down those boundaries that were put up for us and just knock them down – just to see Asians get into clubs.

Now it’s all kind of forgotten because the new generation going out don’t know about the experiences we went through and the battles we fought.”

bbc