Bali’s empty resorts, Thai luxury quarantine and the bizarre post-COVID landscape

Bruno Huber says he is the happiest hotel manager in Bangkok: He actually has guests in his 293-room luxury property. A former Hilton, its legendary garden was once famous for fertility shrines dotted with large, garish wooden phalluses. Today, the garden is every bit as manicured and regal as before, but guests maintain a safe distance from each other as they tramp anticlockwise around the grounds, taking their pre-booked 45-minute exercise breaks.

As the coronavirus pandemic spread across Asia this spring, borders slammed shut to foreigners. Hotels in Thailand — the fourth-largest tourist destination in the world — are languishing. But Huber has ingeniously reinvented the Movenpick BDMS Wellness Resort Hotel, a 4.5-star property, for the age of COVID. It is now among the world’s most desirable quarantine facilities.

“You can call me a prison warden,” Huber laughs, then turns serious. “It was the only way, in these circumstances, that I could continue employing my staff and keep the hotel alive.”

Guests, mainly well-off Thai students and business people returning from abroad, require two negative tests to gain admission — and over 60,000 baht ($1,900) for a solitary two weeks in a deluxe room. Huber is delighted that not one has so far turned positive.

The package includes three meals and two nurse visits per day, plus all the required testing by the adjacent clinic. Guests are pampered with everything from Thai comfort food and special energizing lighting to over 7,000 publications online on PressReader. But there are no visitors at any time, and no alcohol on room service.

Huber, whose silver-white hair is often virtually the only thing that can be seen moving through the Movenpick’s darkened lobby, is prepared to carry on with his new line of business — hosting quarantined arrivals — indefinitely, according to demand.

He sees his new role as a detour in an eclectic career in the hospitality industry. Arriving in 1986, he is one of a group of Swiss and German hoteliers who pioneered management of many of the kingdom’s top properties and helped transform Thailand from a backpackers’ haven to a top-five global tourism destination in three decades. The country recorded nearly 40 million arrivals in 2019.

Over this period, Thailand became a model for many countries in Asia that have sought to replicate its success. The combination of a rising Chinese middle class, the proliferation of budget airlines, and relaxed visa policies have made Asia the fastest-growing destination in the world, with international arrivals increasing annually by an average 6.4% between 2000 and 2018 according to World Tourism Organization data. That growth provided a windfall for economic development for many remote areas endowed with magnificent landscapes or beaches.

Tourism has been an engine for job creation in Asia — The World Travel and Tourism Council estimates one in three net new jobs over the last five years there were created by the tourism industry. And the sector is valuable for its multiplier effect on national economies: Every dollar spent on tourism generates multiples of additional spending, as tourists go shopping, buy souvenirs and dine at restaurants.

Sputtering engine

But the arrival of COVID-19 has rolled these achievements back — in some instances, permanently. Air travel has plummeted to virtually zero as draconian travel restrictions continue. Hotel occupancy in Asia dropped 43% between June 2019 and June 2020 to 38%, according to STR, a hotel industry data provider. The International Air Transport Association estimates that air travel will take until 2024 to emerge from the crisis, and many observers consider that optimistic.

Hotels have already started laying off staff to survive. “I learned long ago never to worry about things I can’t control,” Bill Heinecke, a U.S.-born Thai citizen who runs Minor International, a Bangkok-based hotel and restaurant giant, told Nikkei in May. “All I can control is our response to the crisis. We began laying off people very early — we reacted faster than many international companies. The biggest danger in these crises is to panic. I would like to believe we didn’t. If you know what you should be doing, do it quickly.”

Now, the tourism multiplier that propelled Asia’s growth is working in reverse. In other words, for every $1 million lost in international tourism revenue, a country’s national income could decline by $2 million to $3 million, due to the knock-on effect on other economic sectors that supply the goods and services travelers seek while on vacation, according to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

UNCTAD estimates that global tourism’s sudden collapse could cause losses of up to $3.3 trillion this year when other affected sectors are taken into account — 4.2% of global gross domestic product. And that is if the downturn only lasts 12 months.

“For most parts of the world [including Asia], travel has become, from this huge economic driver, a small shell of its former self,” said Chetan Kapoor, co-founder of Videc, an analytics company focusing on the travel industry.

Tourist businesses in most countries are trying to weather the storm with a combination of government support and ingenuity: Michelin-starred restaurants are now doing takeout, while Thailand has rearranged and increased public holidays to encourage domestic tourism. The government even announced subsidized hotel accommodation with $720 million from the state budget in July, part of a promotion dubbed “We Travel Together.”

Meanwhile, luxury quarantine was not an industry until four months ago. Now, Thailand has just under 5,000 private hotel rooms, providing a sumptuous alternative to more austere state facilities. “We pioneered an alternative to state quarantine by offering true hotel services,” Huber says.

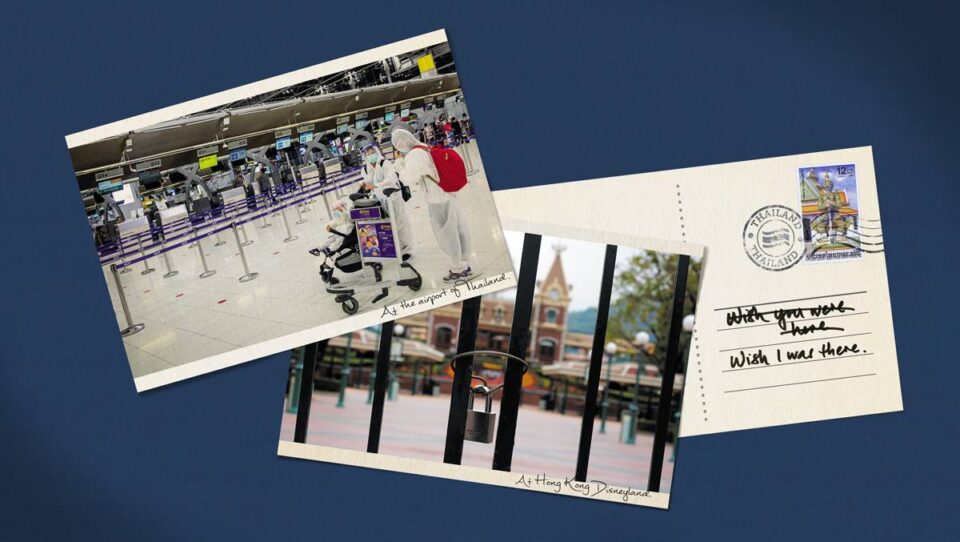

Above: “It was the only way, in these circumstances, that I could continue employing my staff and keep the hotel alive,” said Bruno Huber, hotel manager of the Movenpick and industry veteran. Below: Visitors have the grounds to themselves at Bangkok’s Wat Arun, a wildly popular tourist landmark before the coronavirus pandemic. (Photos by Lauren DeCicca)

Above: “It was the only way, in these circumstances, that I could continue employing my staff and keep the hotel alive,” said Bruno Huber, hotel manager of the Movenpick and industry veteran. Below: Visitors have the grounds to themselves at Bangkok’s Wat Arun, a wildly popular tourist landmark before the coronavirus pandemic. (Photos by Lauren DeCicca)

The road back is steep, however. “On the positive side, the fundamentals of travel and tourism will not change,” said Imtiaz Muqbil, the editor of Travel Impact Newswire, a tourism newsletter. “People will always want to travel. Airlines, airports, hotels, theme parks, tour coaches, convention centers, museums, restaurants, shopping malls will need the revenue stream. Young people will need jobs. Governments will need tax revenue.

“The industry will need to assess the individual market conditions, evaluate the doing-business environment and start adapting to the new distribution, marketing, and payment technologies.”

But while ingenuity may help some business weather the storm for a while, it alone will not bring back the long-haul tourists, who provide the bulk of tourism revenues in virtually every Asian economy. Talk of “travel bubbles” between neighboring countries has produced few results, aside from Malaysia and Singapore reopening their border in August. The Thai government is floating a new strategy, “Safe and Sealed,” that would tentatively open particular areas on Oct. 1, notably the resort island of Phuket. Tourists would still be quarantined for 14 days, and restricted in their movements.

Slowly, it is becoming clear that a tourism industry without some COVID-19 cases is a virtually impossible proposition.

Thailand, for instance, has had an exemplary coronavirus response, with no community transmitted cases since March, fewer than 3,400 cases and 58 deaths. But the economic costs of the strict measures — including a near ban on foreign travelers — have been immense. Some believe that as many as 8.4 million people will end up unemployed. The International Labor Organization believes that up to 6 million workers in Thailand’s hospitality sector will be out of work because of COVID-19. The hidden damage lies in informal sectors, including beach vendors and sex workers. They have little entitlement under the law but are often family breadwinners.

Closing in

The collapse of tourism in country after country has shut off a route out of poverty for some of Asia’s most vulnerable people. In mid-July, acrobats from the Cambodian Circus took to the ring in their first performance since the government shut entertainment venues in March. Created in 1994 as an organization to help children living in poverty, its members perform death-defying stunts nightly for audiences in the provincial capital Siem Reap, on the outskirts of the crumbling temple complex surrounding Angkor Wat.

Before COVID-19, one of their Saturday or Sunday night shows would draw between 500 to 600 spectators, overwhelmingly foreign tourists. Some nights, they’d hold a second performance just to meet demand.

But as the spotlights lit up the arena for their first show in four months, the stands were almost empty.

“There were about four or five people in the crowd,” Srey Bandual, one of the co-founders of the art school Phare Ponleu Selpak, which runs the circus, told Nikkei.

“Like this, we cannot cover our costs.” Performers at a Cambodian circus run by art school Phare Ponleu Sepak: Before tourism abruptly dried up, they would put on shows to an audience of 500 or 600. © Getty Images

Performers at a Cambodian circus run by art school Phare Ponleu Sepak: Before tourism abruptly dried up, they would put on shows to an audience of 500 or 600. © Getty Images

In Cambodia, developing tourism had been an economic strategy pursued with single-minded ambition in the aftermath of the country’s horrific civil war. Helped by a number of foreign nongovernmental organizations, the sector grew rapidly and recorded almost $5 billion in international tourism receipts last year, equivalent to about 20% of its GDP. Reports place the sector’s workforce between 600,000 and 800,000; indirectly, it supports the livelihoods of millions.

But since March, when many countries began shutting down travel, the drop has been precipitous. Arrivals were down 99% in April and 98% in May from the year before, while almost 3,000 tourism-related businesses had closed as of that month, with more than 45,000 workers losing their jobs, according to government statistics.

Bandual says Phare has started reducing salaries and laying off staff. He said that without support, the organization could survive only another six months. The organization runs two circuses — one in Siem Reap and one in Battambang — and an art school. Altogether, they have about 200 staff.

“Some have taken other jobs. Carpenter, plumber, electrician — whatever job they can pick up, they do it,” he said.

“They need money to feed their families. They are desperate.”

Nem Mann is one of those circus performers, as are six other members of his family.

The 24-year-old has been performing since he was 8 years old. The circus, he says, has helped lift his family out of poverty and provide them an education. One of his brothers has performed in Canada. But, as with millions of others in Cambodia, COVID-19 threatens to wipe out what they have gained.

“I’m worried that if COVID-19 continues, we won’t have jobs,” he said.

“Now I’m taking modeling work here and there, but the rest of my siblings don’t have work. They don’t have any money. We eat what we have.”

Damned if they don’t

Faced with economic ruin, a number of tourism destinations have had to confront the calculus of just how many cases — and deaths — they are willing to tolerate in exchange for staying open. Local authorities are often damned if they do and damned if they don’t — two weeks in quarantine is not exactly attractive to international travelers, but the alternative is just as grim; tourists also tend to shy away from coronavirus outbreaks.

“Travelers around the world are definitely eager to get back on a plane for travel, but what has changed is the attitude toward traveling,” said Videc’s Kapoor. “Increasingly, we see that travelers want to know how they are going to remain safe,” he said.

Bali, one of the most popular beach destinations in Asia, is one such tourism spot trying to juggle two quite possibly irreconcilable goals: avoiding an outbreak, while at the same time staving off the economic collapse of the single motor of its economy.

In June, only 10 foreign visitors passed through Ngurah Rai airport, Bali’s main entryway, versus 527,000 in January. Resorts are nearly empty, despite July and August being peak seasons in Bali, coinciding as they do with summer breaks in the northern hemisphere.

“July and August are our lifeline; I usually earned most of my income around these months. But now, there is no guide job at all,” said Anton, 34, as he preferred to be called, who is a French-language tour guide. He has not accompanied a single tourist since early March, when he took a group of three French couples touring the island for a week.

Seeing the danger of economic collapse, Bali Gov. Wayan Koster in early July announced a gradual reopening of the resort island. On July 9, some tourist sites began to reopen for Bali residents. On July 31, the whole island started welcoming back visitors — but only domestic travelers from other parts of Indonesia. That was supposed to serve as a dry run for a full resumption of international tourism originally scheduled for Sept. 11.

Locals have regarded the discussions with unease. Coronavirus cases have increased in recent weeks; some of Anton’s fellow guides are wary of spending time with strangers, as infections remain out of control. “I regret the government’s decision. I was hoping that they would have waited longer [before reopening],” Anton said.

“But I understand why it has to be taken,” he said. “Not everyone is like me; I have some savings to survive for another three or four months, and have no children to support.”

Locals are concerned about how transparent the regional government is being in their effort to welcome international tourists. As of Aug. 24, Bali reported 4,576 coronavirus cases and just 52 deaths, while Indonesia’s overall cases stood at 155,412 with 6,759 deaths. But unlike national epicenter Jakarta, which keeps track of its daily tests, Bali does not.

Bali’s testing activities are “mysterious,” said University of Indonesia epidemiologist Pandu Riono. “Many [Indonesian] regions won’t increase their testing capacity because perhaps they think it can keep them from being declared a ‘red zone,'” Riono said.

Ahead of the planned Sept. 11 reopening, Bali Deputy Gov. Tjokorda Oka Artha Ardana Sukawati met the national police and stressed that there are eight labs in the island province that can perform polymerase chain reaction tests for coronavirus. However, he stopped short of saying how many tests they have performed so far. “Preventive efforts that we’ve done so far are showing improving outcomes,” was as much as he would say.

Riono said Bali exemplifies many Indonesian regional governments: “It seems like there’s nothing going on there. But if Bali is serious with the testing, [the case number] will surely be high.”

Several cabinet ministers had visited the island during the first half of August as part of the tourism reopening campaign. But eventually, with no flight clearance in sight for international visitors, Bali is backpedaling. Koster on Aug. 22 admitted, “The Indonesian government can’t reopen entry doors for international tourists through the end of 2020, because Indonesia remains within the red zone category.”

Hot and cold

Similar experiments to Bali’s are happening throughout Asia. “The major move right now is to nurture and grow domestic and regional travel,” said Jesper Palmqvist, Asia-Pacific director of hotel data provider STR.

But, like in Bali, these programs have often become controversial. Vietnam opened up domestic travel after weeks of zero COVID-19 cases. But in July, more than 80,000 domestic tourists were evacuated from the popular coastal city of Danang and surrounding destinations when a second wave of cases hit the region.

In July, Japan launched some 1.3 trillion yen ($12.2 billion) in travel subsidies, as part of a “Go To Travel” campaign aimed at throwing a lifeline to the pandemic-hit hospitality industry. However, Tokyo almost immediately excluded itself from the program, fearing new outbreaks. The minister of travel and tourism also urged large groups of people to refrain from traveling together.

Tokyo Gov. Yuriko Koike likened the subsidies to “putting cooling and heating systems on at the same time,” amid the city’s recent spike in cases and those in prefectures surrounding the capital. Nikko, a popular daytrip destination from Tokyo: Japan’s capital excluded itself from a massive domestic tourism campaign that launched as coronavirus cases spiked. (Photo by Ken Kobayashi)

Nikko, a popular daytrip destination from Tokyo: Japan’s capital excluded itself from a massive domestic tourism campaign that launched as coronavirus cases spiked. (Photo by Ken Kobayashi)

Japan is looking to domestic tourism to rescue some high-profile investment projects that are facing delays and possible cancellation. One place this is being felt is Sasebo, a small port city of 250,000 in Nagasaki Prefecture, which has seen plans for a casino thrown into turmoil by the pandemic.

The casino and conference center were supposed to provide jobs for the surrounding area, with the project to break ground as early as 2025. Sasebo mostly relies on shipbuilding and related heavy industries. But now, the city faces jittery foreign potential partners and an uncertain investment future. Bidding has been delayed.

Hideki Matsunaga, a member of the local Chamber of Commerce who is one of the leading advocates of the project, said, “I’m aware of the impact of the pandemic, but the regional economy keeps suffering.” Taking into account the thousands of jobs that the resort promises to create, he said the project would act as a “major driver for revitalization.”

If the project fails, he added, “employment will be lost from the city, and the economic decline will be accelerated further in the coming decades.”

The only tourism destination in Asia that has unambiguously benefited from the switch to domestic travel is China. Chinese tour groups used to almost single-handedly prop up Asia’s entire tourism industry, but suddenly, the pent-up wanderlust of the Chinese middle class is being spent at home. Tourism hot spots like Hainan, the vacation island off China’s southern coast, are booming. The street of Soi Cowboy in Bangkok’s red light district, mainly catering to tourists and expatriates, stands empty in August. (Photo by Lauren DeCicca)

The street of Soi Cowboy in Bangkok’s red light district, mainly catering to tourists and expatriates, stands empty in August. (Photo by Lauren DeCicca)

Marriott hotels in Hainan in July even surpassed occupancy of the same month last year, while the hotel chain’s properties in other leisure destinations such as Chengdu and Zhengzhou are recording occupancies at around 80%, said Craig Smith of Marriott International.

In some niches, even international tourism is gradually restarting. China has thrown an economic lifeline to casino capital Macao by allowing some mainland tourists to go there in August. Macao is the world’s most tourism-dependent economy, accounting for 88% of its GDP, according to the WTTC. In Thailand, some medical tourism has resumed, mainly among Chinese couples seeking IVF treatments, though two-week quarantines are still mandatory and the anticipated numbers are not huge.

For now, the thaw is limited. Chattan Kunjara Na Ayudhya, deputy governor of the Tourism Authority of Thailand, said during a webinar in August that talk about travel bubbles had gone quiet. “That talk has not continued so far because of outbreaks in many of the countries we were hoping to get tourists from,” he said.

“I see no signal from the government that the country will reopen this year,” he added.

Silver linings

There has been one clear beneficiary of the crisis: the absence of tourists has certainly been a boon to the environment in many tourism-battered areas. In Thailand, mass tourism has taken its toll on local wildlife and ecosystems. With air pollutants from traffic congestion and industry emissions greatly reduced during the COVID-19 lockdown, few in Thailand could recall times with cleaner air and more beautiful cloud formations on view.

“With rain, wind and lockdown, we are breathing a bit better these days in many parts of Thailand, even though forest fires and open burning of agricultural waste have persisted,” Kakuko Nagatani-Yoshida, a regional coordinator for the United Nations Environment Programme, told Nikkei. “We must find a way to return to a better place in terms of air quality in post-lockdown.”

Rare turtles have come ashore for the first time in decades in Phuket, where exotic crab species have been cavorting along Maya Bay, made famous — and later environmentally devastated — in 2000 by a film starring Leonardo DiCaprio. Maya Bay had already been closed until mid-2021 in an attempt to recover from the ravages of mass tourism. As planes remain grounded at Suvarnabhumi Airport, an unlikely beneficiary has been the environment: In Thailand, skies have cleared and rare turtles are returning to some beaches. (Photo by Akira Kodaka)

As planes remain grounded at Suvarnabhumi Airport, an unlikely beneficiary has been the environment: In Thailand, skies have cleared and rare turtles are returning to some beaches. (Photo by Akira Kodaka)

According to research undertaken by Booking.com, even before the COVID-19 outbreak, there was a noticeable shift in travelers becoming more conscious about the environmental impact they can have. Over 82% of global travelers identified sustainable travel as important to them.

Even after the pandemic is over, tourism is unlikely to return to massive growth, experts say. Just as office workers may find it hard to go back to commuting, many tourists are discovering the joys of staying closer to home.

Cheap long-haul travel will not return for years, if ever. There is speculation that the industry may split into ultraluxury for a few VIP travelers, with mass resorts catering more to domestic tourists. The free-spending foreign travelers that once buoyed the economic future of much of Asia could well be a thing of the past.

“It is going to be a long, hard road back to normalcy,” said Muqbil, the industry newsletter editor. “One thing is for sure: The days of bragging about endless growth prospects from a bottomless pit of tourists are gone forever.”