Late on the night of 4 May, shots rang out in the Indian capital, Delhi, at a sports stadium famous for wrestling.

When the police arrived at the Chhatrasal stadium, they found five vehicles parked outside and a shotgun and three cartridges in the backseat of an SUV. They also found dry blood on bamboo sticks heaped in the parking lot.

There had been a brawl at the stadium involving 18 to 20 people, police said. Three people had been injured and had been taken to hospital. Hours later, a 23-year-old wrestler, Sagar Dhankar, died of his wounds.

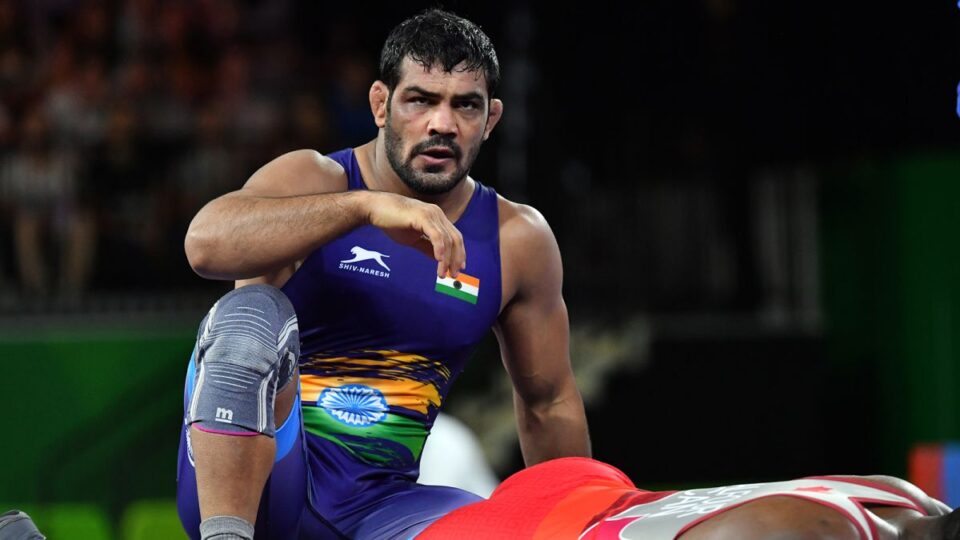

Among the brawlers, police said, was Sushil Kumar, one of India’s most decorated sportsmen. The 37-year-old wrestler is the country’s only two-time Olympic medallist in an individual event and the only Indian to win a wrestling world championship.

This is an extraordinary feat in a country which had won a total of two individual Olympic medals in the last century.

Kumar also holds an official position in the sports department of the Delhi government and lives in a housing complex inside the stadium, where he first began training as a 14-year-old under the tutelage of his former coach, and now father-in-law, Satpal Singh.

For three weeks the police hunted for Kumar. They launched raids and offered 100,000 rupee (£950) reward for any information leading to the wrestler’s capture. On 23 May, Kumar was arrested outside a metro station in Delhi.

He now faces charges of murder, abduction and criminal conspiracy related to the clash at the stadium. The police say they are looking for CCTV footage of the night.

Media has been awash with claims about the brawl being triggered by property disputes, in which the wrestler was involved, and the alleged close links between gangsters and wrestlers.

Kumar denies the charges, his lawyer Pradeep Rana told me. “Two groups of wrestlers were fighting. By the time Kumar arrived at the spot of the clash, they had run away,” Rana said.

“There are no eyewitnesses. Some powerful people are behind the scenes to implicate my client and settle old scores.”

But Kumar’s arrest has shone a spotlight on what many say is the seamier side of wrestling in India.

A wrestler in India is sometimes called a pehelwan, which also means a strongman. Although the word is used loosely, wrestlers have been often accused of mingling with unsavoury characters and getting embroiled in fights.

“We get a bad name because gangsters also call themselves pehelwan in India. And people think wrestlers are gangsters.

We are not,” said Kripa Shankar Bishnoi, a senior wrestling coach and a former partner of Kumar.

But it is also true that wrestling in India appears to have a darker side.

Powered by akhadas (traditional schools, where combatants practice in earthen pits) and dangals (local competitions in both pits and on mats), wrestling is thriving as a mass participation sport.

Delhi itself has hundreds of akhadas, many located in rough neighbourhoods on the outskirts of the city, where rival gangs fight over spoils from property sales.

In villages and small towns, local politicians often fund the dangals. “Sometimes politicians use young wrestlers who haven’t been able to make it big to rough up people they are having a fight with. It’s difficult for a wrestler not to know gangsters,” said Rudraneil Sengupta, author of Enter the Dangal, Travels through India’s Wrestling Landscape.

It is not uncommon for fights to break out during competitions. A wrestling coach, Sukhwinder Mor, is currently awaiting trial for the murder of five people in February, including a rival coach.

Sengupta, a sports journalist, followed Kumar for seven years while researching his book.

The wrestler had rapidly risen from a modest background – his father was a bus driver, and his mother, a homemaker – to become a wealthy sporting icon after his Olympic wins. Like other wrestling stars, he always had a fawning entourage of young wrestlers following him, travelling in a fleet of vehicles and carrying licensed guns, said Sengupta.

“When I asked them when they carried firearms they said it was for protection,” he said. “They had to often travel to dangals in the badlands of northern India and return carrying a lot of cash in prizes.”

By all accounts, Kumar was a fiercely hard-working and cerebral wrestler, leading a near-monastic life. A vegetarian, the 66kg freestyler woke up at the crack of dawn, climbing ropes, grappling in the pit and on mat, and worked out in the gym.

“He was always very competitive, even in football and basketball games after practice,” said Bishnoi, the wrestling coach.

Kumar also helped convert a dingy car parking basement of the Chhatrasal stadium into a brightly-lit Mecca of Indian wrestling, attracting hundreds of young aspirants

. India’s three Olympics medals for wrestling have come from this underground nursery. Kumar looked after budding wrestlers who lived and slept in congested rooms. At a time when most wrestlers were practising in earthen pits, he graduated to mat, where combatants have less traction but more mobility.

At his peak, Kumar was a “graceful, power and supple wrestler …a fascinating combination of violence and harmony,” Sengupta, who followed him over 60 training sessions, said. “I found him very warm and helpful, always helping and training the young wrestlers. I never saw him losing his cool.”

Yet, Kumar was no stranger to controversy. In 2016, Narsingh Yadav, a fellow wrestler, accused Kumar of spiking his food after he failed in a drug test for the Rio Olympics and was banned for four years. An investigation cleared Kumar of all charges.

Kumar’s arrest was a “big setback” for Indian wrestling, said Bishnoi.

Others were not so sure: the sport has made deep roots in India and gets plenty of support. But all agree on one thing: the wrestling star, who fused brains, brawn, and dazzling speed, had unmatched skills and influence.

Wrestling, Kumar told Sengupta once, was “all about anticipation”.

“When I’m on the mat, I’m so filled with this awareness that the slightest touch feels like electricity to my body, and my body reacts to that the same way it would have reacted if I touched a live wire,” he said.

No two fights, Kumar added, were ever the same. Now he faces possibly the toughest fight of his life

bbc.