Thailand does not intervene with foreign exchange rates to gain competitiveness in trade, its central bank chief said on Monday, amid rising concerns that the country may become the first in Southeast Asia to be placed under trade scrutiny by the U.S.

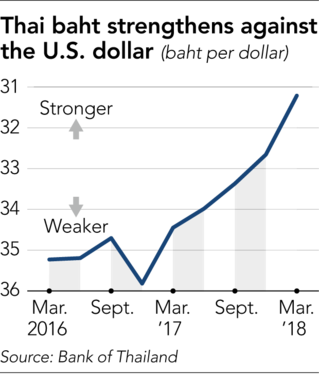

In an interview with the Nikkei Asian Review, Bank of Thailand Governor Veerathai Santiprabhob stressed that the Thai baht had been moving in line with market supply and demand, pointing out that the currency had been strengthening in the past year or so to become one of the best-performing currencies in the region due to capital inflows from advanced economies.

“We have no policies of fixing exchange rates at a particular level or manipulating exchange rate to a particular level,” he said.

With a huge current account surplus accounting for 10.8% of its gross domestic product in 2017 and a trade surplus with the U.S. topping $20 billion, Thailand has already filled at least two of the three criteria that the U.S. Treasury uses to designate a trade partner a currency manipulator.

In the U.S. Treasury’s latest report earlier this month, Thailand was not put on its watchlist due to its small trade volumes, but it has hinted it will expand the list of countries under scrutiny in its next report expected in October.

Veerathai explained that the large current account surplus was due to three factors: cheaper oil imports; a boom in tourism thanks to a huge influx of Chinese travelers; and weak domestic investment.

But as domestic investment is picking up and oil prices are rebounding, Veerathai said that the “current account surplus is adjusting in the right direction,” projecting it would come down to around 8-9% of gross domestic product in 2018.

Thailand’s foreign reserves at the end of 2017 totaled $202.5 billion, a growth of nearly 20% year-on-year. The sharp rise hinted at baht-selling and dollar-buying by the Bank of Thailand.

Veerathai said that the central bank intervened only to tame sharp volatility that could have “much implication” on the country’s economic recovery. “We might have to intervene in the foreign exchange market from time to time, mainly because of the rapid or intense capital inflows,” he said. “It is not our policy to manipulate currencies for competitiveness gain in trade.”

While much of Thailand’s economy depends on trade, the governor voiced concerns over the recent rise of protectionism among larger countries such as the U.S.

He said that although the direct impact of U.S. trade restrictions might be small for Thai products — steel and aluminum, on which the adminstration of President Donald Trump has imposed tariffs, account for less than 1% of the country’s total exports — he was more cautious of the indirect effects.

“The lingering concerns of trade protectionism, and the possibility that it can expand into more serious problems, will definitely pull down investment demand across the globe and that is something I am sure no one would like to see happening,” he said.

Thailand’s economy, which had seen sluggish growth since late 2013 due to political unrest, picked up to 3.9% growth in 2017 on the back of stronger exports. In March, The Bank of Thailand revised upwards its GDP growth forecast for this year to 4.1%, from 3.9%.

As central banks in other parts of the world, including Thailand’s neighbors Singapore and Malaysia, have moved to raise interest rates, some analysts are expecting that the Bank of Thailand will also raise its policy rate which has stayed at 1.5% since 2015. In the latest meeting of the country’s monetary policy committee in March, one of the seven members voted to raise rates by 0.25 basis points — the first time that the MPC did not come out with a unanimous vote since its last rate cut.

Veerathai sees policy normalization as “unavoidable” in the long term. However, citing a weak recovery in rural economies, which are led by farming households, he said that “at this point, the MPC statement is very clear that we see the need to have a continued accommodative policy stance.”

He added that a widening interest rate gap between Thailand and advanced economies such as the U.S. could help “slow down” capital inflows and weaken the baht.