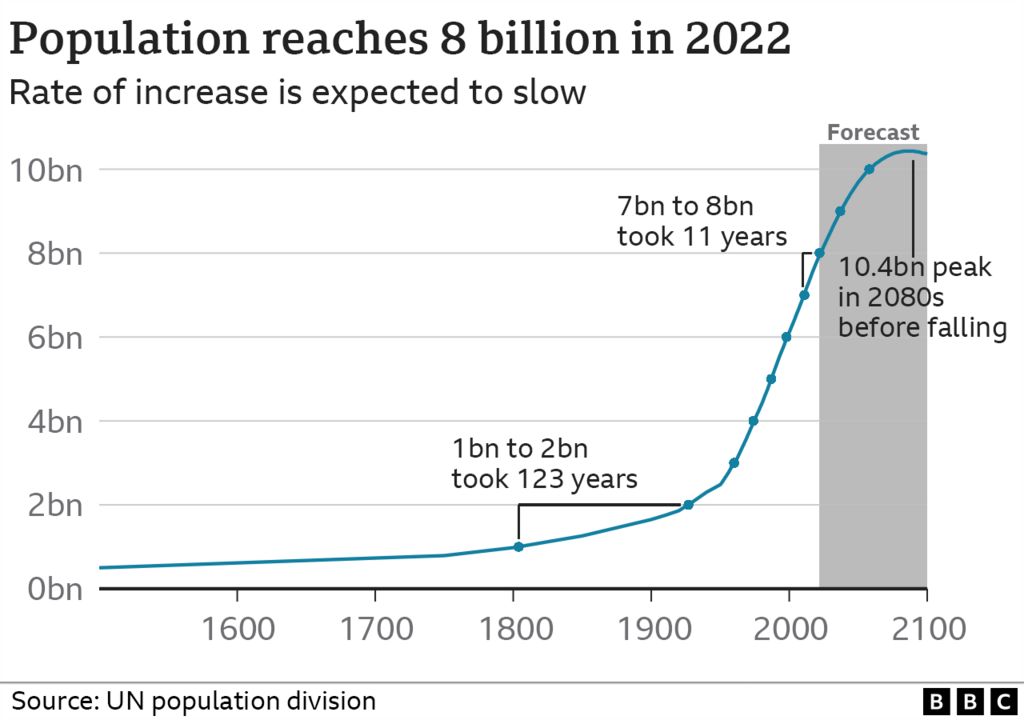

The UN says the world’s population has hit eight billion, just 11 years after passing the seven-billion milestone.

After a big surge in the middle of the 20th Century, population growth is already slowing down.

It could take 15 years to reach nine billion and the UN doesn’t expect to reach 10 billion until 2080.

It’s hard to calculate the number of people in the world accurately, and the UN admits its sums could be out by a year or two.

But 15 November is its best estimate for the eight billion line to be crossed.

In previous years, the UN has selected babies to represent the five, six and seven-billionth children – so what can their stories tell us about world population growth?

A few minutes after he was born in July 1987, Matej Gaspar had a flashing camera in his tiny face and a gaggle of besuited politicians surrounding his exhausted mother.

Stuck at the back of a motorcade outside, British UN official Alex Marshall felt partially responsible for the momentary chaos he had brought upon this tiny maternity unit in the suburbs of Zagreb.

“We basically looked at the projections and dreamed up this idea that the world population would pass five billion in 1987,” he says. “And the statistical date was 11 July.” They decided to christen the world’s five-billionth baby.

When he went to the UN’s demographers to clear the idea they were outraged.

“They explained to us ignorant people that we didn’t know what we were doing. And we really shouldn’t be picking out one individual among so many.”

But they did it anyway. “It was about putting a face to the numbers,” he says. “We found out where the secretary general was going to be that day and it went from there.”

Thirty-five years later the world’s five-billionth baby is trying to forget his ceremonious entry into the world. His Facebook page suggests he’s living in Zagreb, happily married and working as a chemical engineer. But he avoids interviews and declined to speak to the BBC.

“Well, I don’t blame him,” Alex says, remembering the media circus of Matej’s first day.

Since then, three billion more people have been added to our global community. But the next 35 years could see a rise of only two billion – and then the global population is likely to plateau.

Just outside Dhaka in Bangladesh, Sadia Sultana Oishee is helping her mum, peeling potatoes for dinner. She’s 11 and would rather be outside playing football but her parents run a pretty tight ship.

The family had to move here when their business, selling fabric and saris, was hit by the pandemic. Life is less expensive in the village, so they can still afford to pay school fees for their three daughters.

Oishee is the youngest and the family’s lucky charm. Born in 2011, she was named one of the world’s seven-billionth babies.

Her mum had no idea what was about to happen. She hadn’t even expected to give birth that day. After a doctor’s visit she was sent to the labour ward for an emergency Caesarean section.

Oishee arrived at one minute past midnight, surrounded by TV crews and local officials craning over each other to see her. The family were stunned but delighted.

While her father had hoped for a boy, he’s now happy with his three hard-working, intelligent daughters. His eldest is already in university and Oishee is determined to become a doctor. “We are not that well-off and Covid has made things harder,” he says. “But I’ll do everything to make her dream come true.”

Since Oishee was born, another 17 million people have been added to Bangladesh’s growing population.

This growth is a great medical success story, but the rate at which Bangladesh is expanding has slowed enormously. In 1980 the average woman would have more than six children, now it is less than two. And that’s thanks to the focus that the country has put on education. As women become more educated they choose to have smaller families.

This is crucial for understanding where the world’s population is likely to go. The three main bodies that make projections on global population – the UN, the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington and the IIASA-Wittgenstein Centre in Vienna – vary on the gains they expect in education.

The UN says the global population will peak in the 2080s at 10.4 billion but the IHME and Wittgenstein believe it will happen sooner – between 2060 and 2070, at less than 10 billion.

But these are just projections. Since Oishee was born in 2011 a lot has changed in the world, and demographers are constantly surprised.

“We were not expecting that the Aids mortality would fall so low, that treatment would be saving so many people,” says Samir KC, a demographer at the IIASA. He’s had to alter his model because an improvement in child mortality has a long-term impact, as surviving children go on to have children themselves.

And then there are the staggering drops in fertility.

Demographers were shocked when the number of children born per woman in South Korea dropped to an average of 0.81, Samir KC says. “So, how low will it go? This is the big question for us.”

It is something more and more countries will have to grapple with.

While half of the next billion people will come from only eight countries – most of them in Africa – in most countries the fertility rate will be lower than 2.1 children per woman, the number necessary to sustain a population.

In Bosnia-Herzegovina, one of the most rapidly declining populations in the world, 23-year-old Adnan Mevic thinks about this a lot.

“There is going to be nobody left to pay for pensions for retired people,” he says. “All the young people will be gone.”

He has a masters in economics and is looking for a job. If he can’t find one he’ll move to the EU. Like many parts of Eastern Europe, his country has been hit with the double-whammy of low fertility and high emigration.

Adnan lives outside Sarajevo with his mum, Fatima, who has surreal memories of his birth.

“I realised something was unusual because doctors and nurses were gathering around but I couldn’t tell what was happening,” Fatima says. When Adnan arrived, the then UN Secretary General Kofi Annan was there to christen him the world’s six-billionth baby. “I was so tired, I don’t know how I felt,” Fatima recalls, laughing.

Adnan and his mum flick through photo albums. In one a tiny boy sits in front of a giant cake, flanked by men in suits and military khakis. “While other kids were having birthday parties, I was just visited by politicians,” Adnan says.

But there were perks. Being the six-billionth baby led to an invitation to meet his hero, Cristiano Ronaldo, at Real Madrid, when he was 11.He finds it stunning that in 23 years the world population has grown by two billion people.”That’s really a lot,” he says. “I don’t know how our beautiful planet will cope.”