A Bali island was covered in trash. The once-polluted beaches and waterways of Nusa Lembongan have been transformed thanks to a community-run recycling facility.

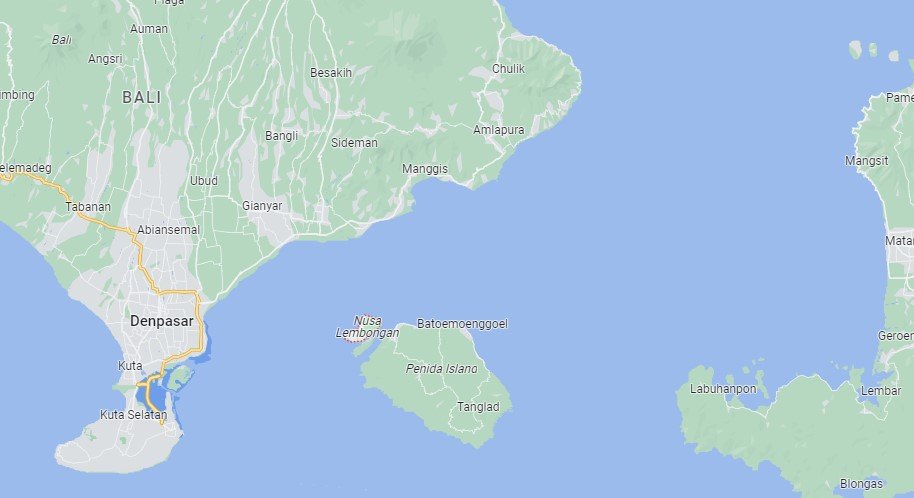

India’s Nusa Lembongan – Five years ago, Nusa Lembongan’s beaches, a paradise island just 30 minutes by speedboat from Bali, were littered with the same type of trash that marred most of Indonesia’s most well-known tourist destination.

Today, Nusa Lembongan’s shorelines are immaculate, and its once-heavily polluted river, which supports a vast network of mangroves, is spotless.

The Lembongan Recycling Centre (LRC), a community-run facility that collects trash twice daily from companies, residences, and waste collection points on the island, then sorts and compacts paper, plastic, metal, and glass for sale, has been credited in major part for the turnaround.

In addition to raising environmental awareness among islands, the project has also given waste a monetary value, providing locals with a financial incentive to clean up their property.

According to Margaret Barry, the Australian creator of the Bali Children’s Foundation, a nonprofit that aids in funding the LRC, “the mangroves were cleared of metal, including old boat engines and motorbikes, when locals learned the metal had value.” Barry said this to Al Jazeera.

The 8,000 residents of Nusa Lembongan have historically subsisted on fishing and seaweed farming. About 20 years ago, when Bali-based surfers and divers who were searching for uncrowded waves and coral reefs discovered the island, things started to change.

Tourism opened up new economic opportunities for Nusa Lembongan, but it also brought with it enormous amounts of inorganic trash. Over time, plastic water bottles, straws, and other trash were thrown away in an alleged temporary landfill on the island, out of the way and out of consciousness of the island’s tourism industry, which is centered on the coast.

The only method the islanders knew of getting rid of the waste was to burn it regularly, which turned the dump into a tiny mountain within a decade.

On a patch of land he owned in the center of the island, Pilot, an islander who goes by only one name like many Indonesians, established a straightforward sorting station for plastic debris in 2016. Only a small portion of the waste produced on the island was recycled, however, due to financial constraints.

A sorting station employee named Putu acquired control of the property in 2017 and built a modest structure there.

The Bali Children’s Foundation, Friends of Lembongan, social enterprise Bali Hope, as well as nearby hotels and restaurants, contributed funds for equipment and personnel, resulting in the birth of the LRC the next year.

The option to send tons of rubbish to be recycled, shipped off the island, and sold, rather than being burned or deposited to a landfill, became available to islanders.

Oktavianus Agustus Pa Njola, an English teacher on Nusa Lembongan who has taken his students to the facility to learn about recycling, told Al Jazeera, “From my perspective, the LRC operates the island is very clean since they collect waste twice every day.” “Rubbish starts to pile up on the side of the road again when they halt for just one day.”

The collaboration of the program, according to Mitchell Ansiewicz, owner of Ohana’s, a beachfront resort on Nusa Lembongan that pays the LRC $50 each month to remove its trash.

“Nusa Lembongan draws a lot of divers, surfers, and yogis—people who often care about the environment, already recycle regularly, and want to make a difference. Throughout the years, several of them initiated programs, such as beach clean-ups, Ansiewicz told reporters

“They didn’t last or didn’t make much of a difference for a variety of reasons; perhaps the correct palms weren’t greased or locals felt like they were being told what to do. However both the local and foreign communities have contributed positively to the LRC. The island’s cleanliness significantly improved when the forces of labor and capital combined.

When the epidemic, tourists ceased, fuel for cars used in garbage collection became scarce, and the majority of islanders reverted back to growing seaweed.

Owner of the Komodo Garden Guesthouse and LRC volunteer Kris said to reporters that the center was ineffective during the pandemic and that everything moved along extremely slowly. “However, now that the local administration, or banjar, has provided us with good cooperation, we have three-wheel vehicles to collect trash and salaries for 18 people, and I now receive monthly payments from hotels and restaurants. We are once again operational now.

A small community permaculture garden and aerobic composting program were introduced to LRC in November. These initiatives generate veggies like eggplant, onions, ginger, and garlic that are resold to restaurants and hotels.

According to Maharus, the head gardener, organic compost is more efficient and secure to use than synthetic fertilizers. Locals on Nusa Lembongan claim that the majority of islanders do not segregate their trash at home, therefore not enough of it is being produced to grow the pilot-sized garden.

In Nusa Lembongan and throughout Indonesia, combining organic and inorganic garbage at home continues to be a concern. Indonesia is the second-largest producer of food waste in the world after Saudi Arabia, according to data published by the government-run National Solid Waste Management Information System, which reveals that 42% of waste produced in the nation is organic.

According to the World Bank, recycling facilities in Indonesia only manage to collect less than 5% of the waste produced as a result of this cross-contamination in garbage. The recycling rate for plastic is only slightly higher at 7%.

According to LRC’s stakeholders, efforts are ongoing to find more effective means of encouraging islanders to separate their trash.

Putu, the LRC manager, said, “We are trying to give the community guidance and understanding to sort rubbish from their houses and even provide reciprocity in the form of economic value to stimulate the community in handling waste.” Yet on this island, we need to be really patient and talk to the people more to help them appreciate the value of separating waste at the source.

Director of the Center of Waste Management Indonesia in Jakarta, Bayu Indrawan, cited LRC as an excellent illustration of a small community taking initiative to address its trash issue.

According to Indrawan, who spoke to reporters, “there are many community-based projects like this in Indonesia since the central government, which has an existing waste-to-energy technology plan to handle the problem, is not in a good situation to implement it on a national scale.”

They are focused on correctly handling waste in cities like Jakarta and Surabaya since they are out of places to put it. They are already out in Jakarta.

Indrawan, though, remains optimistic about the future.

We found Nemo! Hiding while we scuba dived Nusa Lembongan!#nusalembongan #nemo #findingnemo pic.twitter.com/aPHSoo48Qa

— Bali Indonesia (@balilocal) March 1, 2023

He declared, “The government is finally on the right track. “Indonesia now has better waste management than it did ten years ago. I believe we can improve much farther, but it all depends on how people see things.

On Nusa Lembongan, meantime, there are indications that younger generations’ perspectives are shifting.

Since only organic materials may be used to create compost, we must separate inorganic and organic materials. Komang, a 12-year-old student who uses green and red trash cans to separate trash at school, told Al Jazeera that if they are intermingled, it poses a problem.

Komang acknowledged that her parents don’t recycle much at home, but she said she will when she is older and living on her own.

Komang’s teacher, Pa Njola, claimed that her pupils give her hope for the future.

Pa Njola assured us that if we can educate the youth and increase their consciousness, the issue would be resolved in the following generation.